Almost every time I’m talking about measuring how much time we spend on value-adding tasks, a.k.a. value, and non-value-adding stuff, a.k.a. waste, someone brings an example of refactoring. Should it be considered value, as while we refactor we basically improve code, or rather waste, as it’s just cleaning after mess we introduced in code in the first place and the activity itself doesn’t add new value to a customer.

It seems the question bothers others as well, as this thread comes back in Twitter discussions repeatedly. Some time ago it was launched by Al Shalloway with his quick classification of refactoring:

The three types of refactoring are: to simplify, to fix, and to extend design.

By the way, if you want to read a longer version, here’s the full post.

Obviously, such an invitation to discuss value and waste couldn’t have been ignored. Stephen Parry shared an opinion:

One is value, and two are waste. Maybe all three are waste? Not sure.

Not a very strong one, isn’t it? Actually, this is where I’d like to pick it up. Stephen’s conclusion defines the whole problem: “not sure.” For me deciding whether refactoring is or is not value-adding is very contextual. Let me give you a few examples:

- You build your code according to TDD and the old pattern: red, green, refactor. Basically refactoring is an inherent part of your code building effort. Can it be waste then?

- You change an old part of a bigger system and have little idea what is happening in code there, as it’s not state-of-the-art type of software. You start with refactoring the whole thing so you actually know what you’re doing while changing it. Does it add value to a client?

- You make a quick fix to code and, as you go, you refactor all parts you touch to improve them, maybe you even fix something along the way. At the same time you know you could have applied just a quick and dirty fix and the task would be done too. How to account such work?

- Your client orders refactoring of a part of a system you work on. Functionality isn’t supposed to be changed at all. It’s just the client suppose the system will be better after all, whatever it means exactly. They pay for it so it must have some value, doesn’t it?

As you see there are many layers which you may consider. One is when refactoring is done – whether it’s an integral part of development or not. Another is whether it improves anything that can be perceived by a client, e.g. fixing something. Then, we can ask does the client consider it valuable for themselves? And of course the same question can be asked to the guys maintaining software – lower cost of maintenance or fewer future bugs can also be considered valuable, even when the client isn’t really aware of it.

To make it even more interesting, there’s another advice how to account refactoring. David Anderson points us to Donald Reinertsen:

Donald Reinertsen would define valuable activity as discovery of new (useful) information.

From this perspective if I learn new, useful information during refactoring, e.g. how this darn code works, it adds value. The question is: for whom? I mean, I’ll definitely know more about this very system, but does the client gets anything of any value thanks to this?

If you are with me by this point you already know that there’s no clear answer which helps to decide whether refactoring should be considered value or waste. Does it mean that you shouldn’t try sorting this out in your team? Well, not exactly.

Something you definitely need if you want to measure value and waste in your team (because you do refactor, don’t you?) is a clear guidance for the team: which kind of refactoring is treated in which way. In other words, it doesn’t matter whether you think that all refactoring is waste, all is value or anything in between; you want the whole team to understand value and waste in the same way. Otherwise don’t even bother with measuring it as your data will be incoherent and useless.

This guidance is even more important because at the end of the day, as Tobias Mayer advises:

The person responsible for doing the actual work should decide

The problem is that sometimes the person responsible for doing the actual work can look at things quite differently than their colleague or the rest of the team. I know people who’d see a lot value in refactoring the whole system, a.k.a. rewriting from scratch, only because they allegedly know better how to write the whole thing.

The guidance that often helps me to decide is answering the question:

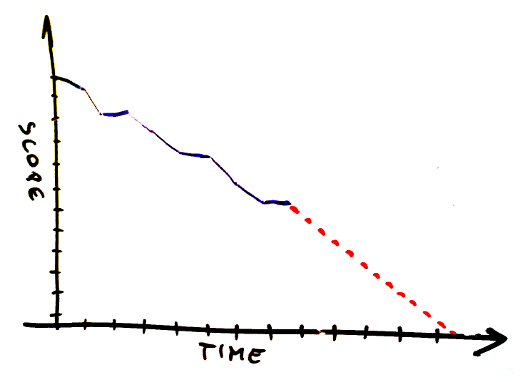

Could we get it right in the first place? If so then fixing it now is likely waste.

Actually, a better question might start with “should we…” although the way of thinking is similar. Yes, I know it is very subjective and prone to individual interpretations, yet surprisingly often it helps to sort our different edge cases.

An example: Oh, our system has performance problems. Is fixing it value or waste? Well, if we knew the expected workload and failed to deliver software handling it, we screwed this one up. We could have done better and we should have done better, thus fixing it will be waste. On the other hand the workload may exceed the initial plans or whatever we agreed with the client, so knowing what we knew back then performance was good. In this case improving it will be value.

By the way: using such an approach means accounting most of refactoring as waste, because most of the time we could have, and should have, done better. And this is aligned with my thinking about refactoring, value and waste.

Anyway, as the problem is pretty open-ended, feel invited to join the discussion.