In the first part of this series, I focused on why autonomy in a workplace is a critical ingredient if we want to stay relevant. Not only is it a response to the nature of everyday work, with the increasing significance of remote work and the rise of AI, but it is also an emergent outcome of the large-scale evolution of the economy.

However, if there is a universal warning that should be attached to the advice suggesting decentralizing control, it should be the following.

It’s never as simple as “give people more autonomy.” The way people act in a decentralized system depends on a broader culture, which one should consider before giving everyone more power.

Purpose

One common theme in the discourse on organizational culture is purpose. A shared theme that people and teams aspire to change into reality.

By the way, when considering joining any company, I recommend asking about their purpose. In fact, I’d ask different people this very question and see whether their answers are aligned.

“Making more money” is not a purpose. It’s a tactic. Ditto “increasing value for shareholders.” If you want to send a man to the moon, that’s a great purpose. But it doesn’t have to be that big. I’m a fan of honest aspirations like “creating a healthy workplace that sustains a few dozen employees and their loved ones,” too.

Aside from its strategic role, or impact on motivation, purpose has a role in the discussion about autonomy. It is the force that encourages alignment of all the efforts happening in an organization.

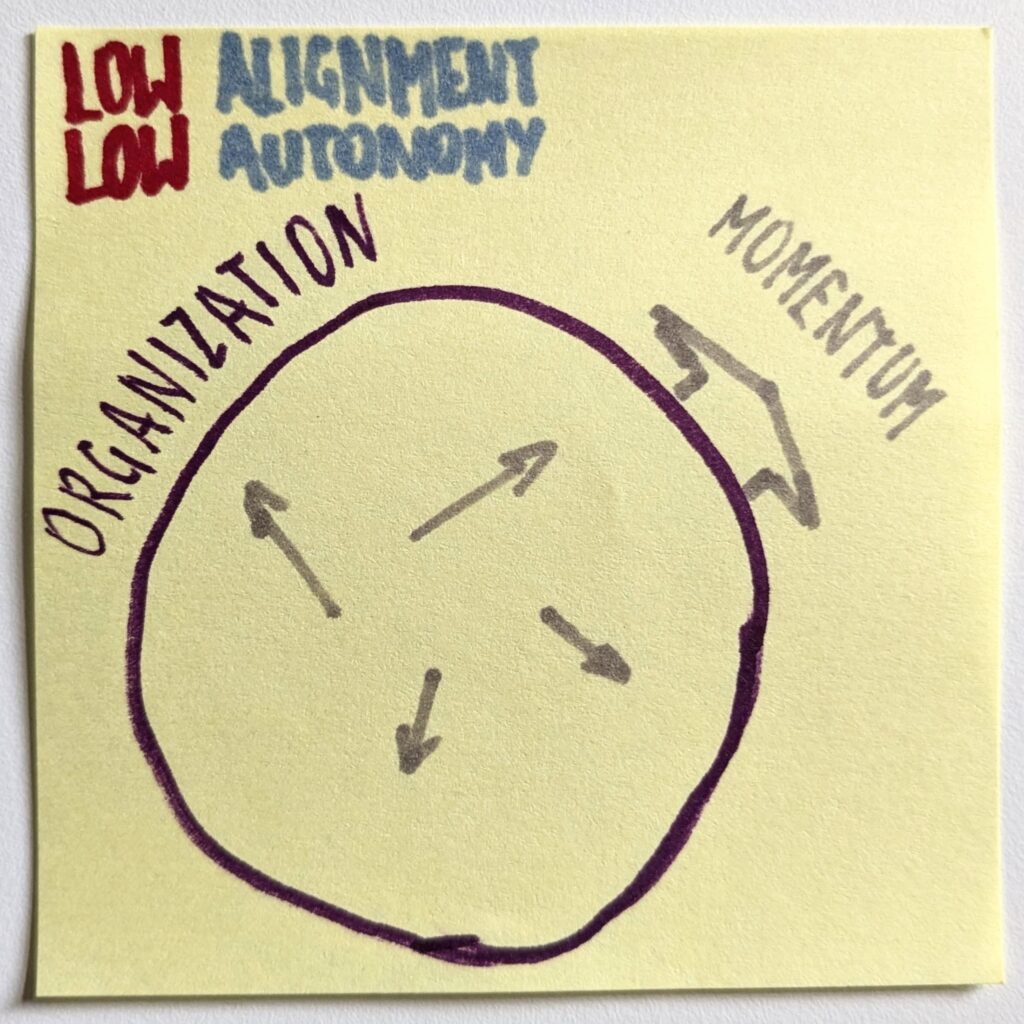

Misalignment

Imagine a company guided by the “making more money” aspiration. People would naturally see different, sometimes contradicting, ways of generating revenues. They’d be pulling in different directions.

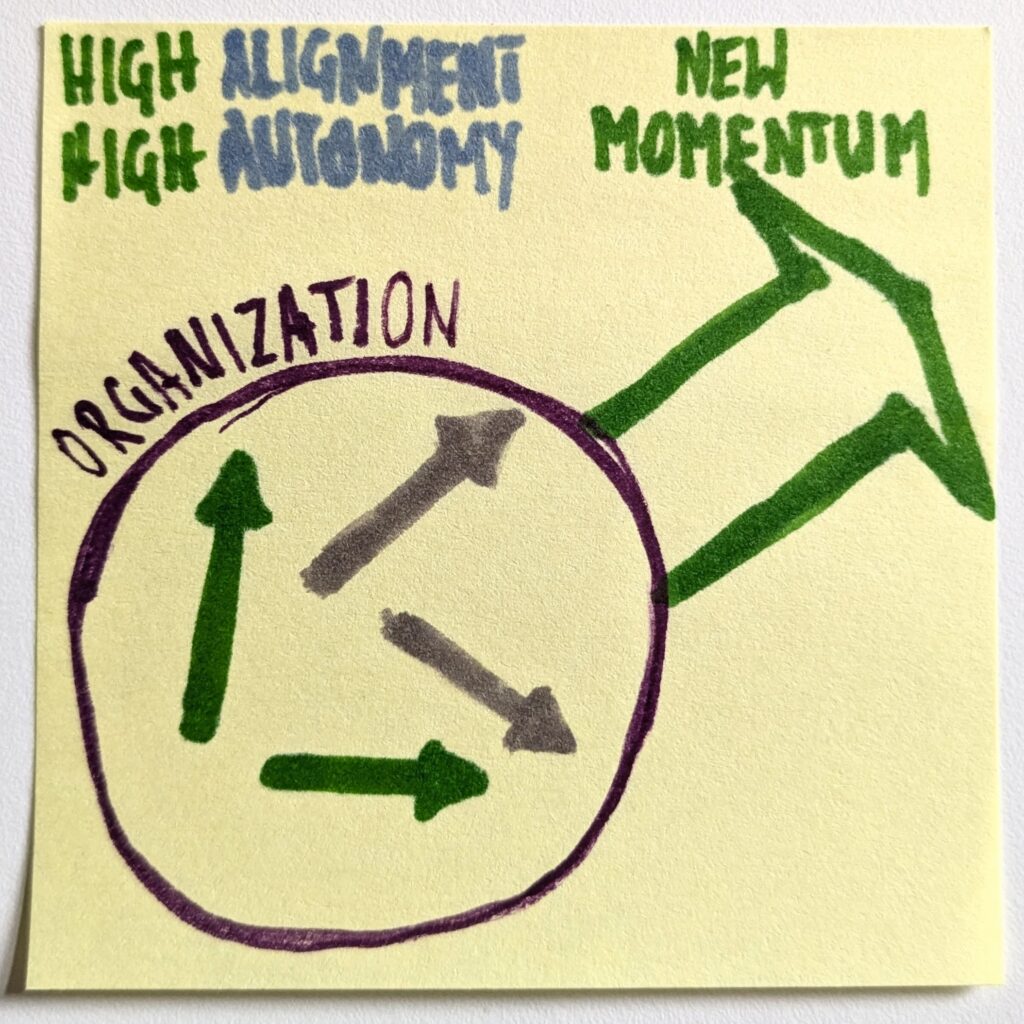

Using a physical metaphor, we could consider a circle as the whole organization and arrows within as different individuals pursuing different goals.

All those forces combined would create some momentum. The company would be slowly moving wherever the push is strongest.

What would happen if we gave people more autonomy in such a setup? It is the equivalent of giving every individual more influence over the whole company. Each force vector would become stronger.

Now, everyone has better leverage, but the combined effect on the organizational momentum is marginal. The reason is obvious. It’s all the contradicting priorities. People try to push in different directions.

Alignment

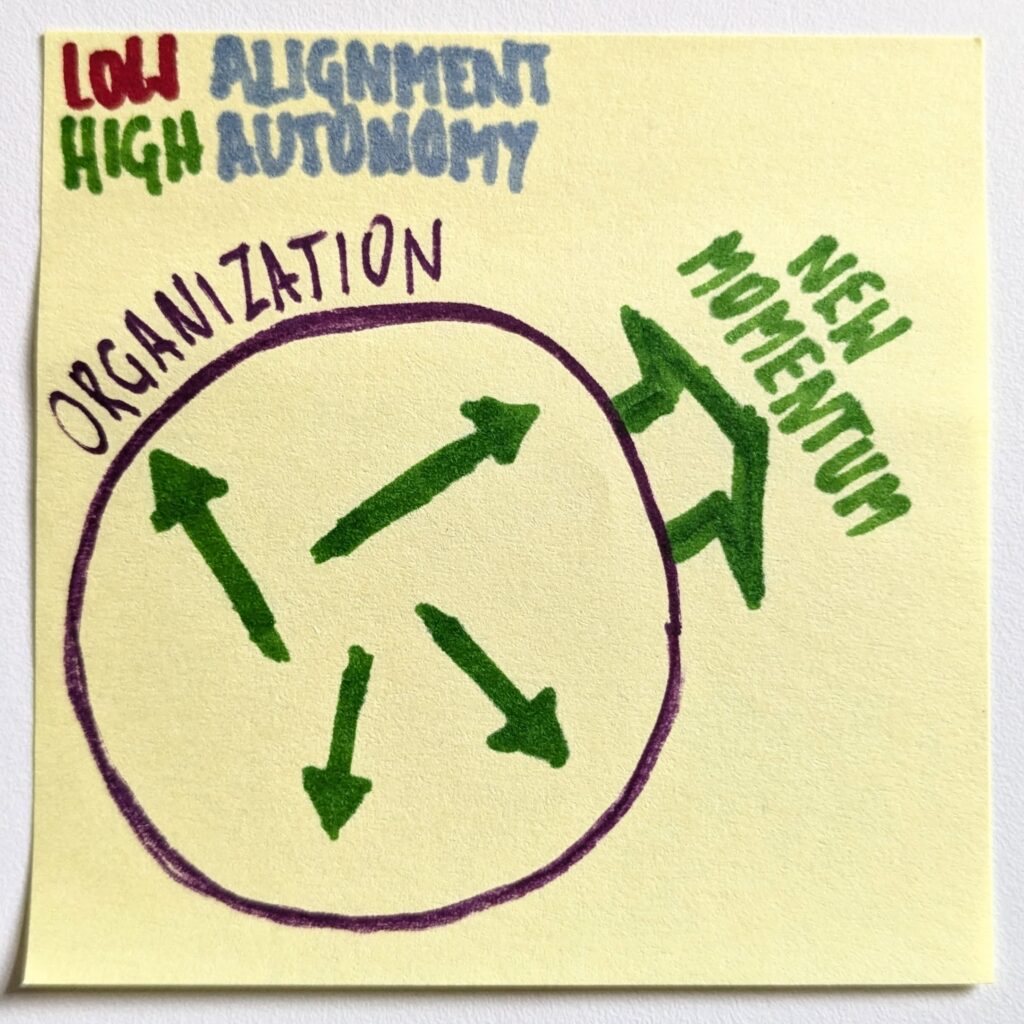

In contrast, we can start in exactly the same situation. However, instead of pursuing the agenda of distributed autonomy, we’ll begin with an attempt to sync up everyone’s efforts.

It would mean getting more arrows to point in a similar direction. I don’t expect a perfect alignment. Every individual has their own goals, which would never be matched perfectly with an organization’s goals. But we can get closer.

The basic tool we have is the purpose. Once it’s clear to everyone what that is, two things will happen. Some people will adopt it and adjust their actions to help achieve it. It’s as if they redirected their vector more toward the desired direction.

Others will figure that they’d rather keep pushing where they have before. For them, it would be clear they wouldn’t get much support. The odds are they’ll leave soon. If our HR does even a half-decent job, whoever comes in their place would be better aligned with the purpose.

One way or the other, we’d get more people rowing in (roughly) the same direction.

That itself changes the organizational momentum significantly. Not only did we remove the opposing force, but we also added a supporting one.

If we follow up with increasing autonomy in this setup now, we will maximize the gains.

Again, everyone has bigger leverage, but thanks to synchronized efforts, the impact is so much more significant.

Alignment First

One could argue that we can achieve the same outcome independently of the order of changes. After all, if we refocused everyone’s efforts after increasing autonomy, the end game would look the same.

In theory, yes. In practice, achieving alignment in such a manner is much less likely and more difficult.

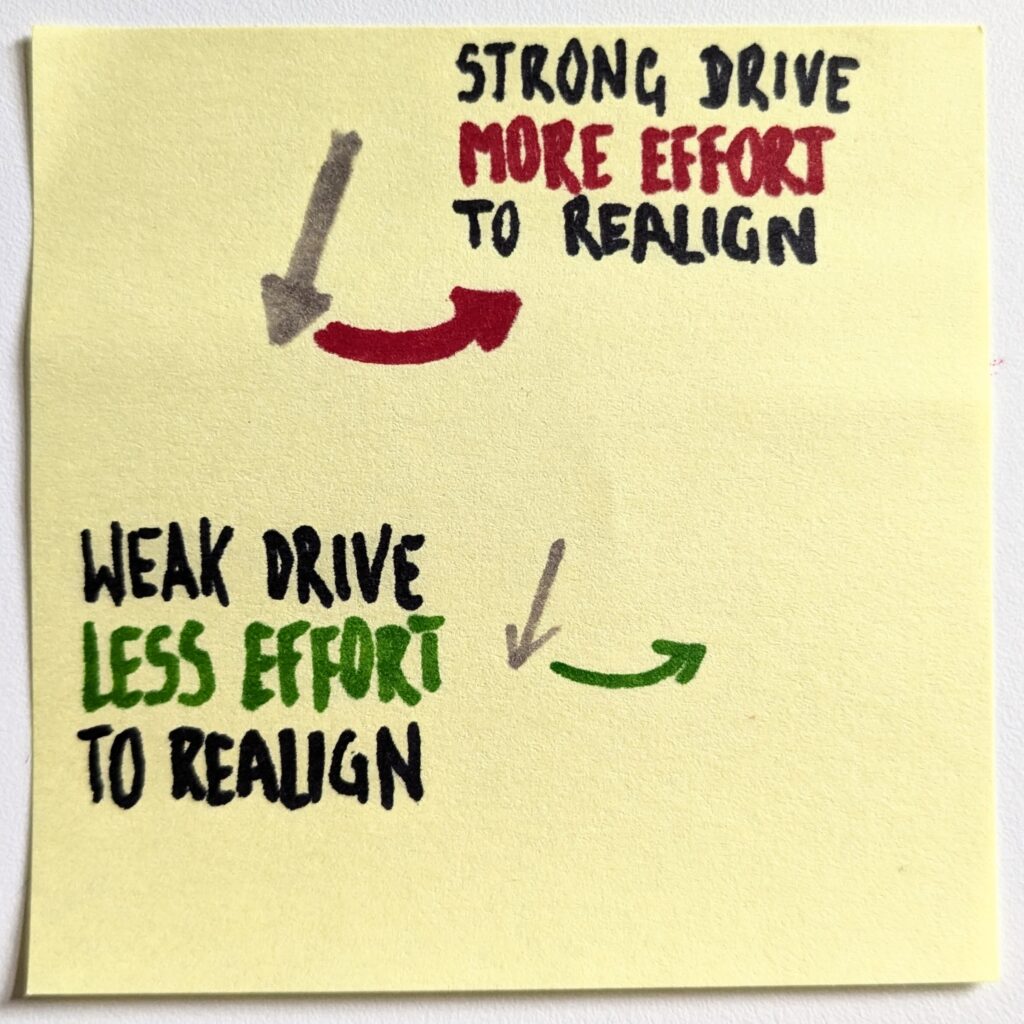

Each vector is a representation of somebody’s drive. The stronger it is, the harder it is to redirect it significantly. Think of the arrows as if they had weight proportional to the force they represent. With bigger weights, it simply requires more effort to align the vectors.

In some cases, alignment will be impossible altogether. We extend our individual expectations to the whole organization. It’s like saying, “I want to pursue this agenda, and thus, I want my company to enable that.” While we would rarely, if ever, express it with these exact words, that’s a prevalent theme in conversations happening around job changes (exit and job interviews alike).

Bigger arrows tend to break before we can realign them to a significantly different direction.

Alignment versus Autonomy

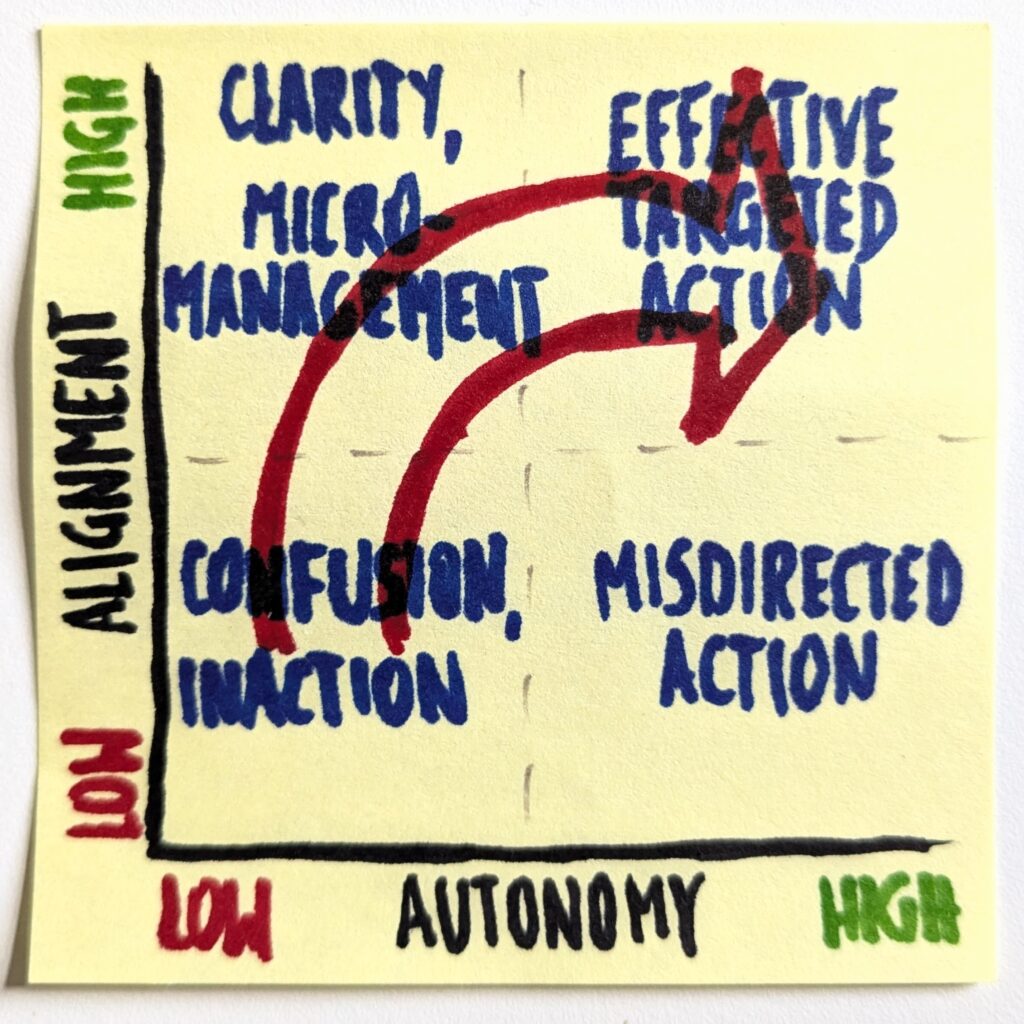

There’s a fantastic depiction of the relationship between autonomy and alignment proposed by Stephen Bungay in The Art of Action.

He plots a two-dimensional plane with our culprits defining the axes.

In an environment with low autonomy and alignment, we won’t see much action. People will neither feel empowered, nor they would have a sense of clarity. You can expect a lot of confusion and minimal tangible outcomes.

If we stick to low autonomy but increase alignment, we will have clarity about the goals. However, the actions will still be carefully managed and controlled. It would be a typical micromanagement environment. Not the most inspiring workplace in my book.

On the opposite end, there’s a low-alignment, high-autonomy environment. There will be a lot going on in such an organization. The problem is that much of that effort will be misdirected. Some of it may be actively counterproductive.

Finally, we have our most desired quadrant with high alignment and autonomy. That’s where we have clarity about the goals, and people act without waiting for permission. Their actions, thus, will be both targeted and effective.

Interestingly enough, Stephen Bungay doesn’t stop by showing what we should expect in each type of environment. He also suggests the best path from the bottom left to the upper right corner.

Unsurprisingly, this path leads through increasing alignment first and only then distributing more autonomy.

I can personally attest it’s a good way, as we did the opposite at Lunar. The price we paid for neglecting alignment was steep. There was a load of interpersonal conflicts, which became a borderline tribal war, and 20% of the company left in the aftermath. Show me a leader who’d willingly drive their company there.

Big Picture

If there were only one big-picture suggestion, I’d couple with my strong encouragement to make distributed autonomy a central piece of organizational culture, it would be about alignment.

Decentralizing control means everyone gets more power over a company and everything it does. That may only get us promising results if everyone rows (roughly) in a similar direction.

We won’t get that unless we explicitly work on alignment. Or are extremely lucky.

I tend not to rely on the latter.

This is the second part of a short series of essays on autonomy and alignment. Published so far:

Pivotal Role of Distributed Autonomy

Feel free to subscribe/follow here, on Bluesky, or LinkedIn for updates.

I also run the Pre-Pre-Seed Substack, which is dedicated to discussing early-stage products.