I’d love to get a beer each time I hear a story about management imposing a change on teams and facing strong resistance. It would be like an almost unlimited source of that decent beverage. Literally every time I’d fancy a beer I’d be like “Hey, does anybody have an agile implementation story to share?”

One common excuse is that people don’t like the change. That is surprising given how adaptable humankind has proven to be. I rather subscribe to the idea that people don’t mind the change; they don’t like being changed.

Unfortunately being changed part is the story of oh so many improvement initiatives. Agile implementations are among most prominent examples of these change programs of course.

So how is it really with responding to changes?

First, it really helps to understand typical patterns of introducing change. The model I find very relevant is Virginia Satir’s Change Model. Let me walk you through it.

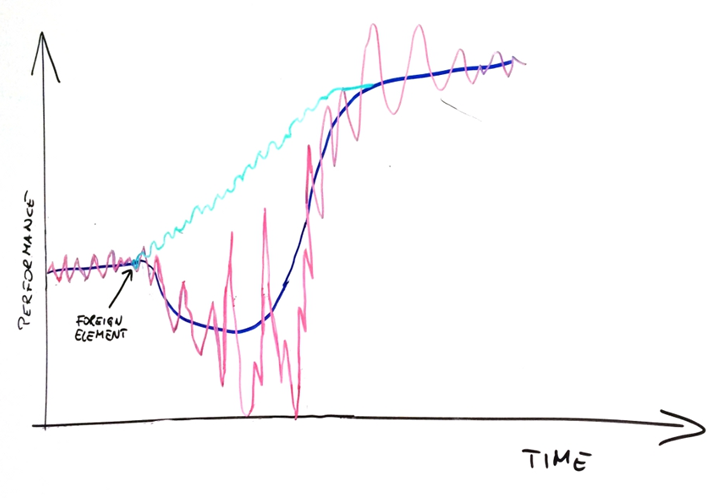

We start with existing status quo that translates to a performance level. Then we introduce something new, which we call a foreign element.

Then we see an expected improvement and they lived happily ever after. Actually, not really. In fact whenever I draw that part of the model and ask what happens next people intuitively give pretty good answers.

After introducing a change performance drops.

It is kind of obvious. We need time to learn how to handle a new tool, practice, method or what have we. Eventually, we get better and better at that and we start seeing the results of promised improvements. Finally, we internalize the change and the cycle is finished.

Because of its shape the curve is called a J-curve.

It is an idealized picture though. In reality it is never such a nice curve.

What we really see is something much bumpier. It is bumpy already when we maintain status quo. It gets much bumpier when we start messing with stuff. It’s not only that rough average goes down but also worst case scenario goes down and by much more.

It’s pretty much chaos. In fact, that’s exactly how this phase is called in the original Virginia Satir’s model.

An interesting observation we can make is that the phase called resistance is a short one that happens just after introducing a foreign element. Does it mean that we should expect resistance against the change to be short-lived?

Yes and no. Yes, if we consider only “I’m not even going to try that new crap” type of resistance. It is typically driven by lack of understanding why the whole change was proposed in the first place. There is however the whole range of behaviors that happen later in the process that we would commonly call resistance too.

Some people aren’t ready to see, even temporary, drop in performance and once they face it they propose to get back to the old status quo. When facing a stressful situation many people retreat back to what they know best and the old ways of doing things is exactly what they know best. There are also those who are impatient and not willing to give people enough time to learn the ropes. The last group often includes managers who funded the change in the first place.

In either case the result, eventually, is the same. More resistance.

Inevitably we reach a pivotal moment. We’ve been through the bumpy ride for quite some time already and yet we haven’t gotten better. In fact, we’ve gotten worse. Not only that. We’ve gotten worse and less predictable. The whole change doesn’t seem like such a good idea after all.

So what do we do?

Of course we reverse the change and go back to the old status quo. Oh, and we fire or at least demote that bastard who tricked us into starting the whole thing.

One interesting caveat of the whole process is that a change is not always simply reversible. When we changed specific behavior and yet didn’t get expected outcomes reverting the behaviors may be difficult if not impossible.

For the sake of the discussion let’s assume we are lucky and the change is reversible. We are back to the late status quo and we simply wasted some time trying something new. Oh, and we built a stronger case for resisting the next change. We petrified the existing situation just a little bit more.

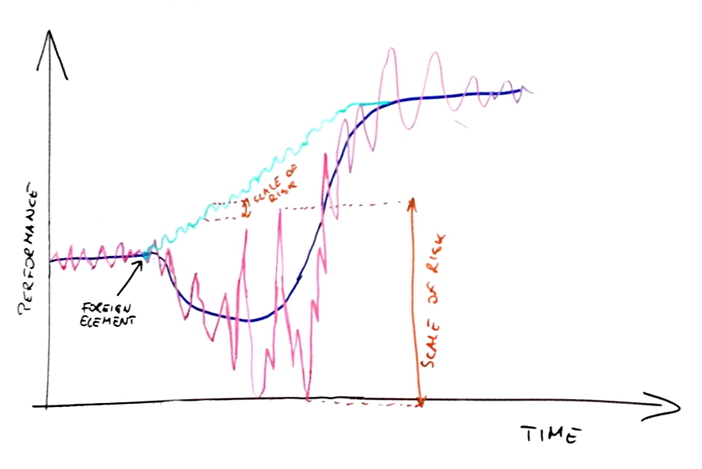

One reason why changes are reverted so often is the perceived risk of the change.

Pretty good proxy for perceived risk is predictability. Typically the more unpredictable a team or a process is the more risky it is considered. In this case, the important thing that comes along with a foreign factor is how much predictability changes. Not only does performance drops but it also becomes much less predictable.

While the former alone might have been bearable, both factors combined contribute to the perception that the change was wrong in the first place.

There is another dimension that is very interesting for the whole discussion. It is the scale of change. How much we want to change the existing environment: team, process, practices, etc.

We can imagine a series of small changes, each modifying the context only slightly. The whole series lead to a similar outcome as one big change rolled out at once.

We can call one approach evolutionary and the other revolutionary. We can use inspiration from Lean and call evolutionary approach Kaizen and revolutionary one Kaikaku.

Fundamentally the J-curve in both approaches would be shaped the same. The difference is in the scale. The revolutionary change means one big leap and rolling out all the new stuff at once. This means a single big J-curve.

The evolutionary approach introduces a lot of tiny J-curves one after the other. In fact it is possible to have a few of changes run concurrently but let’s not complicate the picture any more.

What are the implications?

Let’s go back to the scale of the risk we undertake. With Kaikaku unpredictability we introduce is much higher than what we’ve seen in the late status quo.

Kaizen on the other hand typically go with the changes small enough that we don’t destabilize the system nearly as much. In fact it is pretty likely that unpredictability introduced by each of the small changes will be almost invisible given that we don’t deal with fully predictable process anyway.

The risks we take with evolutionary approach are much more bearable than ones that we deal with rolling out one big change.

That’s not all though.

Another thing is how much destabilization lasts. In other words what is cycle time of change.

Big change, naturally, has much longer cycle time as it requires people to internalize much more new stuff. It means that exposure to the risks is longer. Given that the risks are also bigger it raises the odds that the change will be reverted before we see its results.

With small changes cycle time is shorter and so is exposure to the risks. Again, not only are the risks much smaller but also they are mitigated much faster.

One last thing worth mentioning here is that so far we optimistically assumed that all the proposed changes have positive outcome. That is not always true.

With the evolutionary approach even if some of the changes don’t yield expected results we still gain from introducing others. With a revolutionary approach each part that doesn’t work simply increase likeliness of reverting the whole thing altogether.

It is not to say that Kaizen is always superior to Kaikaku. In fact both evolutionary and revolutionary approaches have their place. Stuart Kauffman’s Fitness Landscape helps to explain that.

Imagine a landscape that roughly shows how fit for purpose your organization is. It should simply translate to factors such as productivity etc. The higher you are the better.

The simplest and safest way to climb up would be to make small steps uphill.

While the approach works very well, eventually we reach a local peak. If we continue our small steps in any direction it would result in lower fitness for purpose. Simply said we wouldn’t perform as well as we did at the peak.

If we look only at the closest terrain we might as well say that we’re already perfect and there’s no need to go further.

Obviously, someone saying that wouldn’t be treated seriously. Well, not unless we are discussing a patient of a mental facility.

The solution is seen when we look at the big picture. If we moved to the slope of another hill we can get better than we are.

That’s exactly when we need a big jump. It doesn’t have to automatically land us in a better situation than the one we’ve been at initially. The opposite would often be the case. What is important though is that we land on the hill that is higher. That translates to bigger potential for improvement.

Once there we can retreat back to good old strategy of small steps that allow us to climb up. Eventually we reach the peak that is higher than the previous one. Then we can repeat the whole cycle looking for even a bigger hill.

Of course, similarly to the case of J-curves the picture here is idealistic in a way that each change, be it small or big, is a successful one. In reality it is more of experimentation. Some of the changes would work, some not.

As you might have guessed, small steps here represent the evolutionary approach or Kaizen. A big jump is an equivalent of revolutionary change or Kaikaku. Depending on the context one or the other will be more useful.

In fact, there are situations when one of the strategies will be basically useless. That’s why introducing change without understanding current context is simply begging for failure.

One more implication of the picture is that, given lack of any other guidance, evolutionary approach is both less risky and more likely to succeed. That’s why I prefer to start with when I’m unsure about the context which I’m operating within.

One last remark on the Fitness Landscape. What you’ve seen here is a heavily oversimplified view. In reality fitness landscape wouldn’t be two-dimensional. Stuart Kauffman discussed it as three-dimensional model although I tend to think of it as of a multi-dimensional model.

It means that each change can improve our situation in some dimensions and have an opposite result in others. We will have different combination of effects in different dimensions – some more desirable and some less.

If that wasn’t enough the whole landscape is dynamic and it is continuously changing over time. In other words, even after reaching local optimum we will need further continuous improvements to maintain our fitness for purpose. The peak will be moving over time.

I know the post got long by now (thank for bearing with me that far by the way). This is however the starting point for the discussion why introducing the change very often triggers resistance. It provides pretty good explanation why some many improvement initiatives fail. This is also one of my answers to the question why many agile or lean adoptions are doomed to failure from the day one.

Trying to significantly change an organization without understanding some underlying mechanisms is simply begging for frustration and failure.

Finally, understanding the change models will influence the choice of the methods and tools we’d use to drive our change programs.