I shared one of those quick thoughts on Bluesky as a knee-jerk reaction to yet another message encouraging startups to get on a fast-growth path.

As luck would have it, Matt Barcomb challenged me on that remark. It turned into an exchange, where we quickly started uncovering deeper layers of strategy and portfolio decisions.

Survival versus Growth

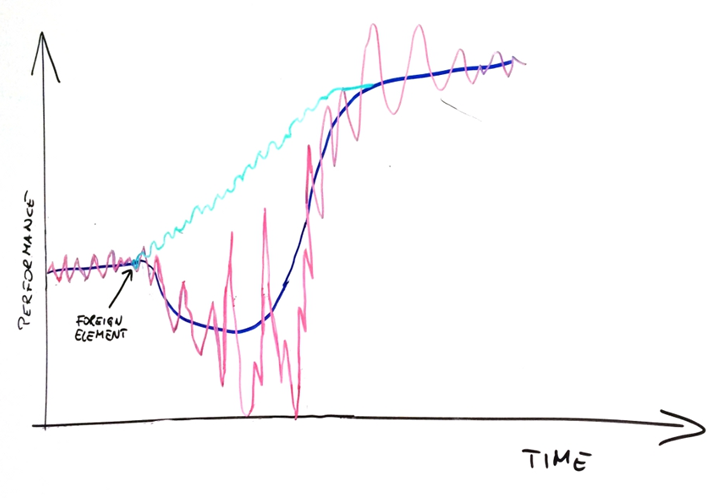

The starting point is a basic observation that there are situations where survival and growth are aligned, even dependent on each other. However, there are also cases where this assertion doesn’t hold, up to a point where growth is harmful.

As a metaphor, no species in nature grows infinitely. While a tree sapling’s survival may depend on its growth, making the process indefinite would compromise the tree’s resilience.

Organizations work similarly, even if Bezoses and Musks of this world would deny it. That is, as long as we are willing to consider standard rules of the business game.

There’s obviously the too big to fail phenomenon, which we’ve seen in action many times. However, it applies only to very few companies, and even when it applies, the subjects of the theory don’t end up any healthier at the end of treatment.

For the rest of us, we may accept that growth and survivability are not always aligned.

What follows is that when forced to choose, we should select survival over growth. If we live to see another day, we can return to growing tomorrow. The opposite doesn’t work nearly as well.

Long-term versus Short-term

However, as Matt points out, prioritizing survivability may lead us toward short-termism. We may always play it safe, and as a result, miss potential opportunities for big wins.

Missing big opportunities may, in turn, be as well an existential threat, except it would develop in the long term. Consider the infamous Kodak digital photography fiasco as a perfect example.

By the way, that example showcases that survivability is as much a short-term concern as a long-term one.

Still, I understand that the “focus on survival first” mantra likely biases us toward what’s immediately visible in front of us. So, let’s explicitly consider survivability and time horizon as two separate dimensions.

Opportunistic Thriving

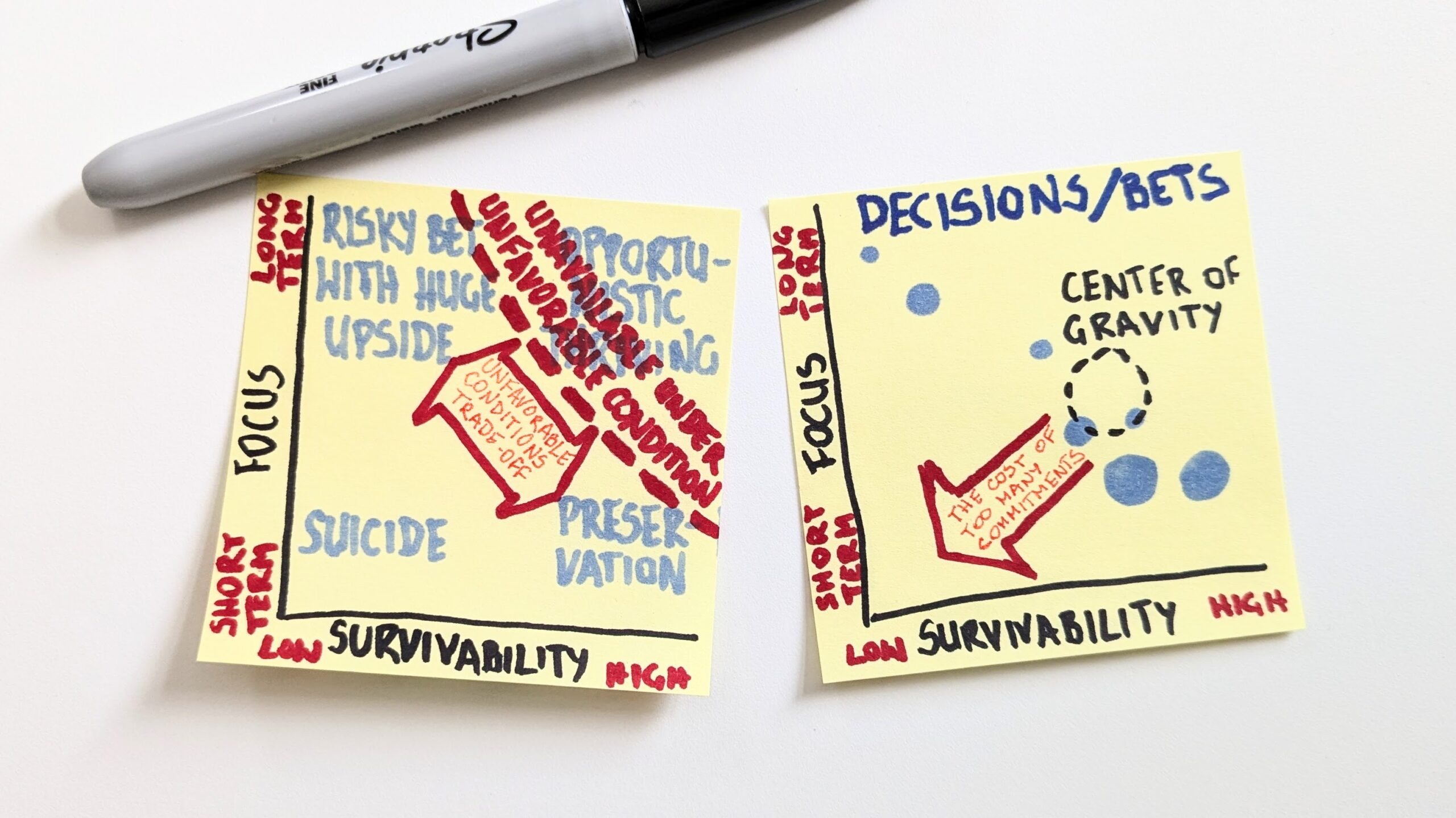

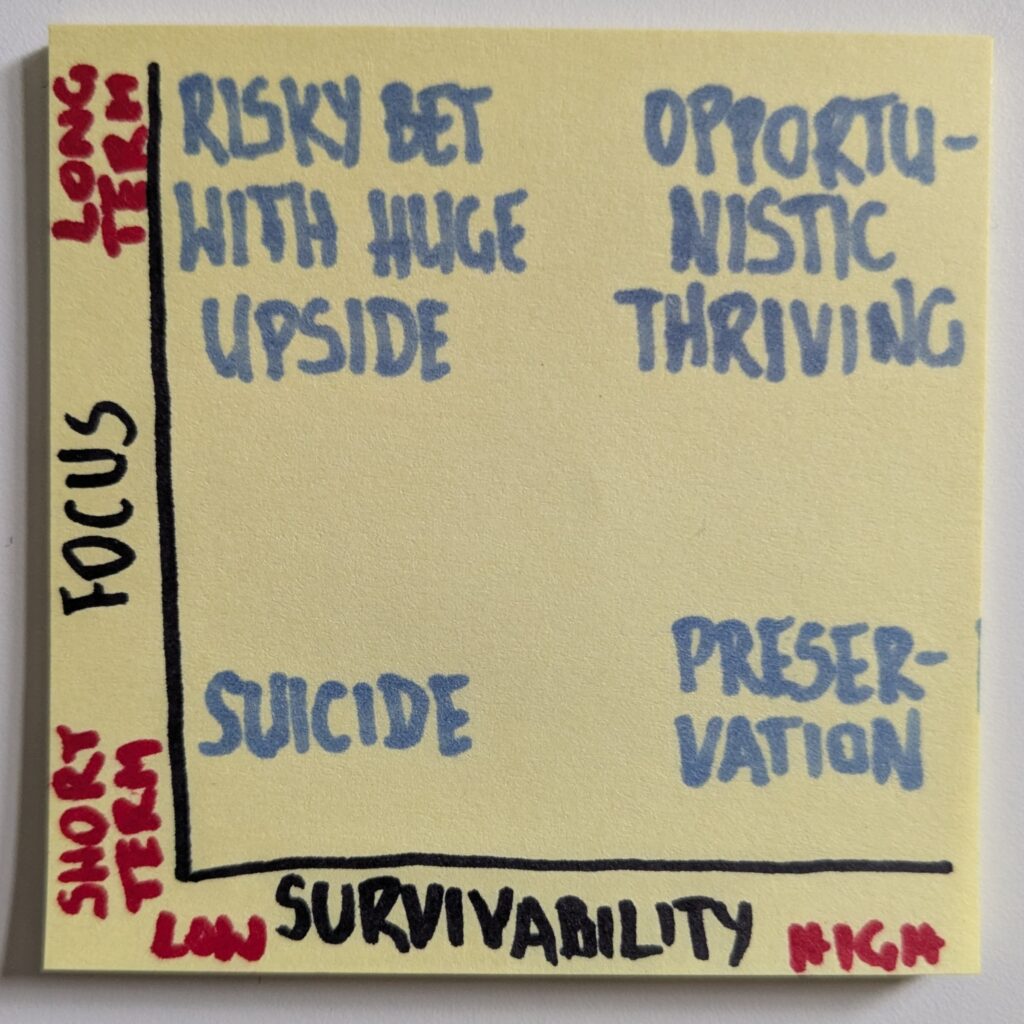

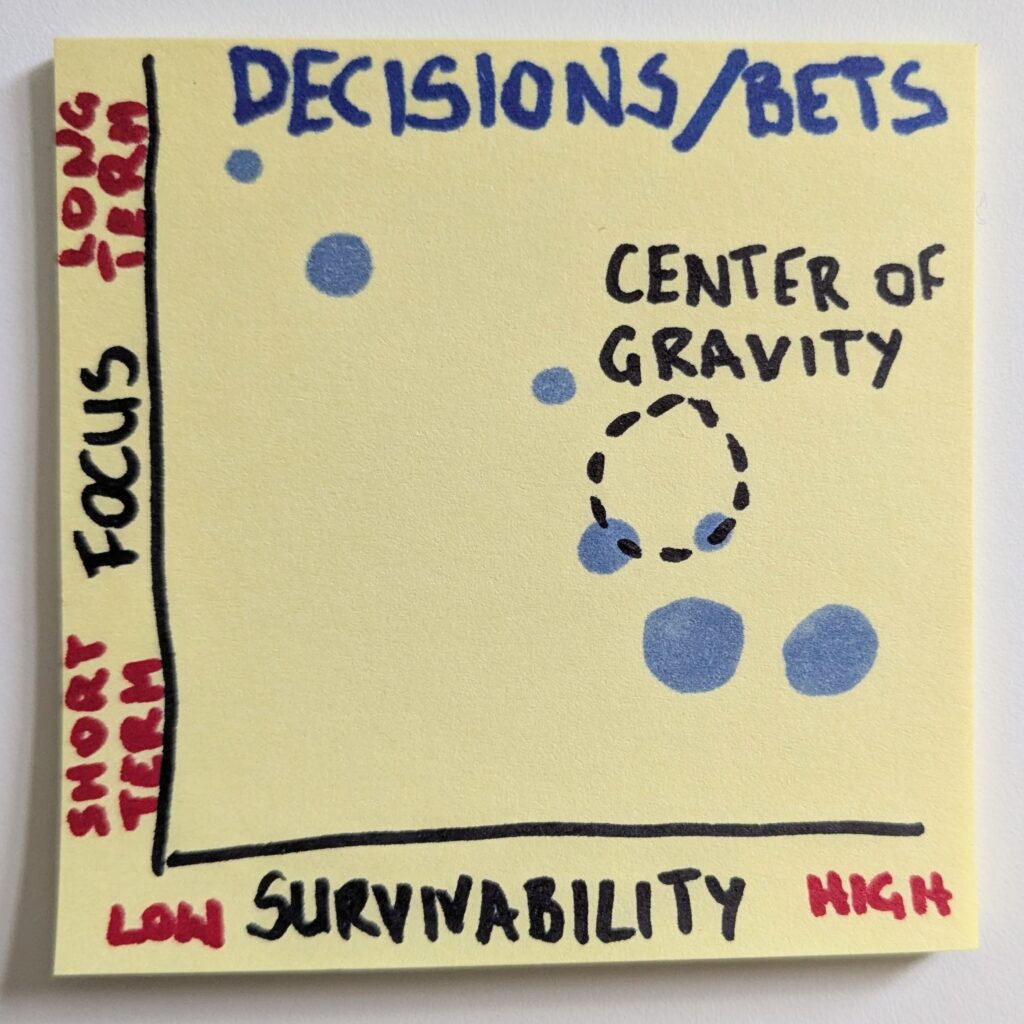

We can consider any combination of low or high survivability with either short-term or long-term focus.

Any strategy threatening the company’s existence and falling into a short time frame would be suicidal (bottom left of the diagram). No sane organization would consciously venture into this territory.

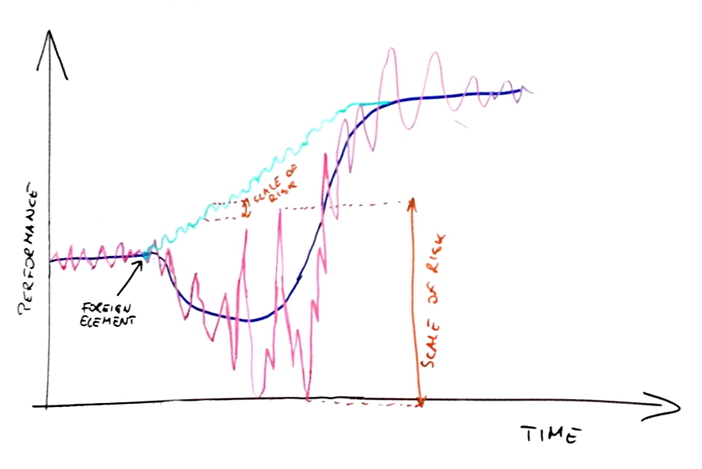

We may want, however, to stick with potentially dangerous plans with a long-term focus. This would be true when a risky move also has a huge potential upside (upper left part of the diagram). In this case, the scale of the possible gain would justify our risk-accepting strategy.

That’s the latter part of the “sure things and wild swings” approach, also known as the barbell strategy proposed by Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

However, if we go for the wild swings, we want to overcompensate them with sure things (Taleb suggests a 9:1 ratio). These safe bets consider primarily a predictable future and focus on preservation (bottom right of the diagram).

If we combine the two, we land with something we can call opportunistic thriving (upper right of the diagram). We would mix some high-risk bets with a largely conservative strategy and exploit emerging chances for growth, new business, etc.

At the end of the day, we align growth with survival, right?

Hold your horses…

Unfavorable Conditions

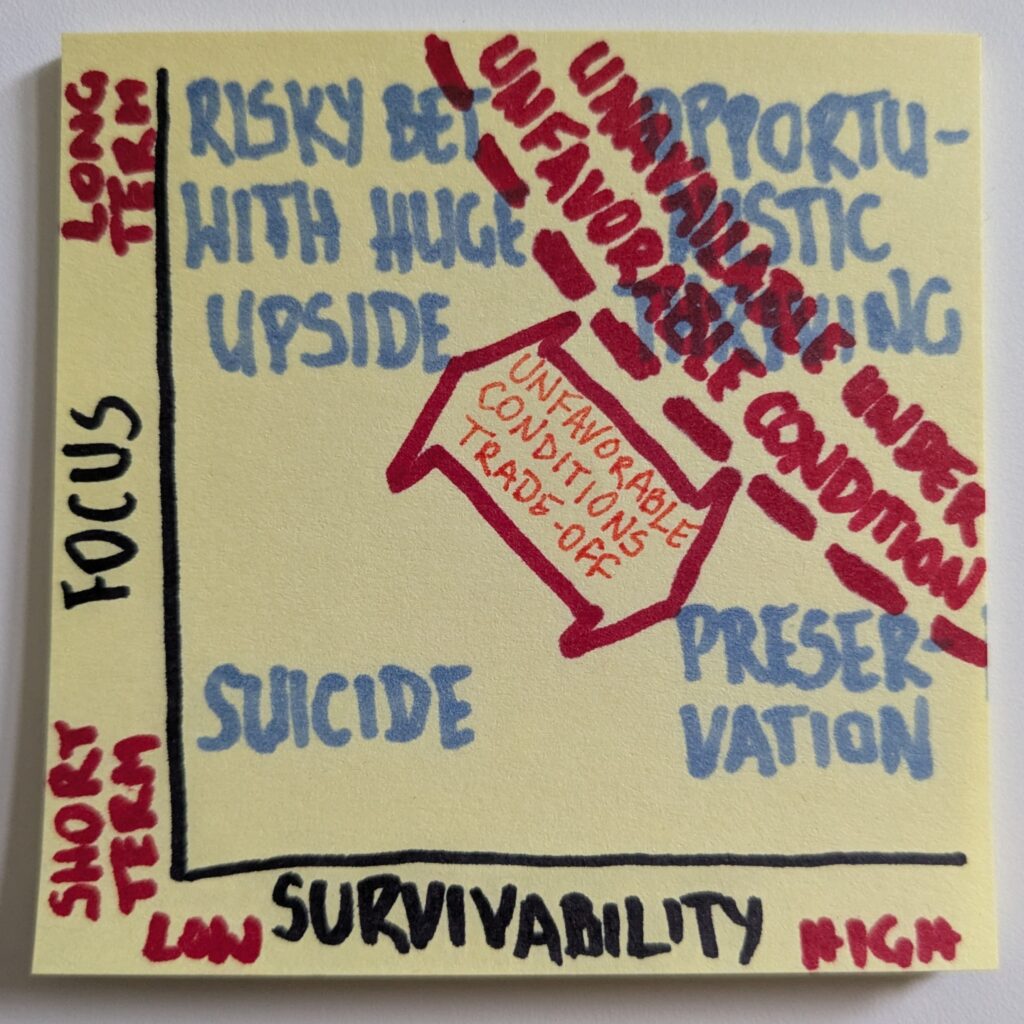

We’re free to explore all options if the conditions are supportive, i.e., the company is already in a safe place and has resources to allocate freely among different options.

But what if we had to make a choice? What if opportunistic thriving wasn’t an option? What if we had to make a trade-off between preservation and risky bets with huge potential upside?

Such a situation would happen when we face unfavorable conditions. One classic example would be whether to retain the team when a downturn hits the company.

Sticking with the proven team means maintaining options for the rebound once an opportunity arises. Here and now, however, we sustain the costs and, thus, incur financial losses.

Playing the preservation scenario would mean layoffs and improving the financials in the short term. It would also trigger all the additional costs of rebuilding the team once the unfavorable condition is over.

Sometimes, the trade-off is a point on a scale, e.g., how many people we lay off. Other times, it is binary, e.g., whether to engage in a risky endeavor.

In either case, it would be a choice to prioritize long-termism over preservation or vice versa.

Available Options

If we assess that situation from a helicopter perspective, we realize that not all the options are available.

To stick with the example of layoffs, we’d like to sustain the team and not incur losses. That would place us in the desired opportunistic thriving area.

A simple fact that we consider what to do means it’s not an option. In other words, the part of the landscape becomes unavailable.

We’d love to be as far into the upper-right part as possible, but that’s precisely the space that becomes inaccessible first. The greater the challenges an organization faces, the farther the unavailable area reaches.

In other words, under unfavorable conditions, we’re forced to make these difficult trade-offs.

Decision Portfolio

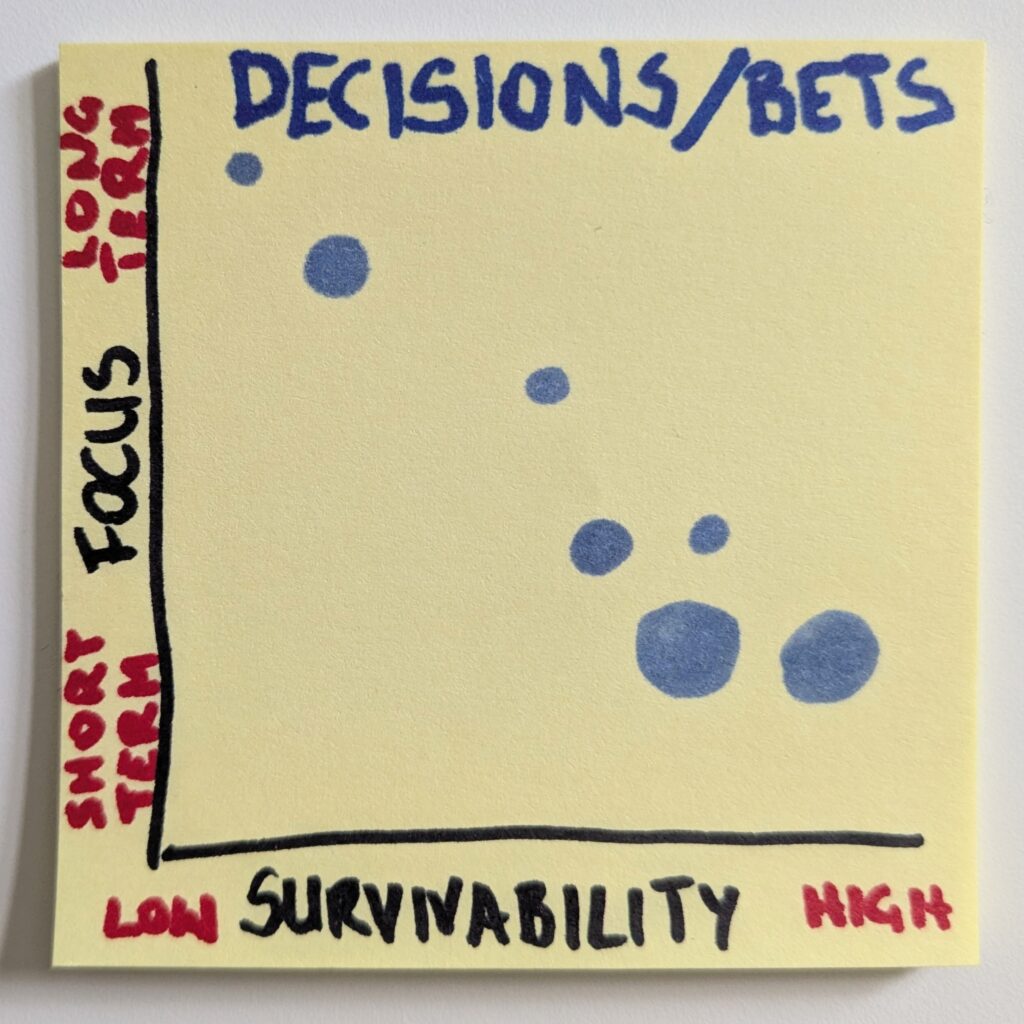

But wait! While any single decision may force us to choose, the whole portfolio of decisions provides an opportunity for a diverse distribution. That way, we can hedge our risks and, through that, push the “unavailability line” back.

That’s what the barbell strategy is all about. We actively distribute our investments across the landscape. It’s like Moneyball applied to business decisions.

Whenever you can’t get one ideal bet (hire a star, in Moneyball terms), make a few non-ideal ones that, when combined, would deliver a comparable result (hire a few role-players with the right skills/stats, in Moneyball terms).

Center of Gravity

All the decisions (or bets) create a center of gravity. Interestingly, it won’t necessarily be a simple output of the weight of the bets (the size of the dots in the diagram) and their relative position.

More forces are in play here.

The right combination of investments may push the center of gravity in the desired direction (up and to the right). Again, in Moneyball terms, it’s like winning having a team of underdogs.

From an organization’s perspective, what interests us most is how any decision in our portfolio affects the center of gravity. That one risky project with low chances of succeeding may be just what we need to improve our long-term relevance. Even if that swing is really wild.

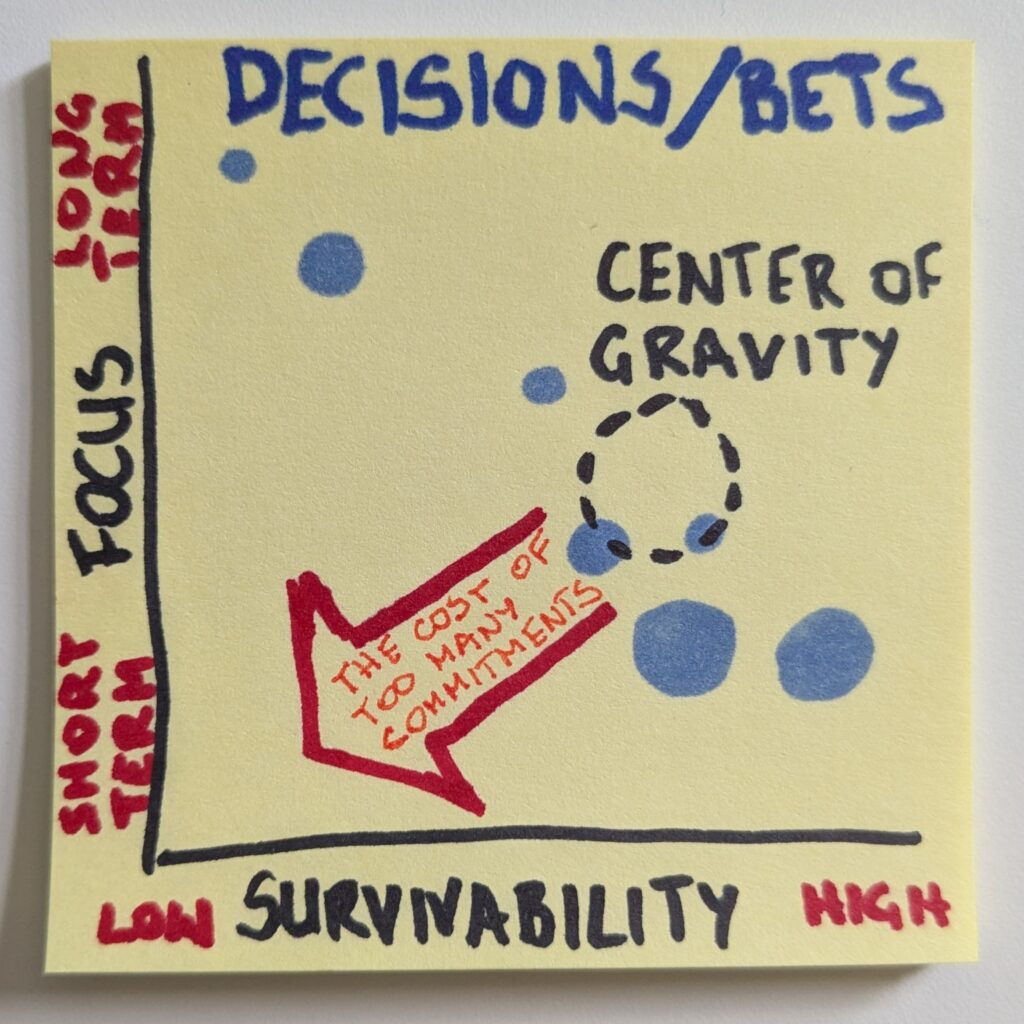

Cost of Too Many Commitments

A brute force tactic of having a diverse enough decision portfolio may be considered. That, however, would create a whole different set of problems.

In the past, I wrote about how too many projects at the portfolio level is a major issue for any organization. I considered how portfolio decisions are, in fact, commitments. I analyzed how overcommitment affects the Cost of Delay and can ruin the bottom line.

It all boils down to the same conclusion: too many commitments are detrimental to (organizational) health.

To visualize it in the landscape we created, we need to add a pulling force. It will move the center of gravity toward the bottom left corner of the diagram. Yes, straight down to our Death Valley.

The strength of this pulling force will be proportional to the scale of overcommitment. And the relationship between the two will be exponential.

The more bets we make, the lower the chances we’ll be able to deliver on any. Once we are already overloaded, adding more commitments will make the situation increasingly perilous.

So, the balance we aim to strike is to have sufficient diversity in our decisions and, simultaneously, to have as few commitments as possible.

The Startup’s Challenge

The entire discussion with Matt began with my remark on the startup ecosystem, pushing aspiring entrepreneurs to grow at all costs.

While the reasoning stands true for startups—especially early-stage startups—two observations make the consideration more challenging for them.

First, by definition, they start under unfavorable conditions. And they stay so for a better part of their lifecycle. As a result, the simple shot for opportunistic thriving is unavailable for them from the outset.

Second, the degree to which the conditions are unfavorable for early-stage startups is far greater than what established companies face. There’s no core business to rely on just yet. The runway is typically short as the availability of funding remains limited.

The environment is challenging enough that the diversity of the bets portfolio must be compromised. And that’s precisely where my original thought falls into place.

Fledgling enterprises, way more than established businesses, will be forced to choose between preservation and wild swings exclusively. The latter is typically characterized by a strong push for rapid growth.

If that’s the choice, I’d go for survival. After all, dead companies don’t really grow.