In one role or another I often help teams to try Kanban out or just to help them to create their task board or Kanban board. There is an interesting pattern I observe.

First thing is happening when a team discusses what columns should appear on the board. It is very common, and advised, to start working with Kanban with exactly the same process you already have in place. You could expect people would know it by heart. It should be really quick: “we do this, this and that, so it goes to the board.”

Well, it appears that “process we follow” is pretty ambiguous most of the time. There are discussions whether something is a separate stage of the process or rather a part of the bigger task etc. People find they don’t really know where to put specific tasks as they’re floating depending on a number of factors. It appears the process isn’t really defined or not everyone is on the same page or people understand their tasks differently.

Note: it all happens without any change in the process. No wonder why many process transitions are failed. What do you expect when people don’t really get how they’re working at the moment, let alone how they’re supposed to work?

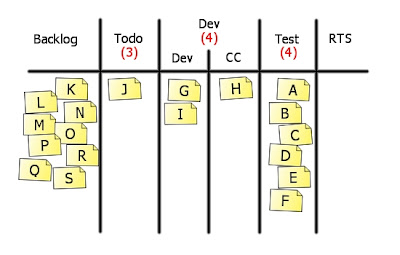

Then there is another observation. In the long run Kanban boards tend to become more and more complex. As teams work with their boards they add something to the structure more often than they remove anything. That’s perfectly understandable. When people learn better their process and the board which should reflect the process they have more ideas how to improve it. So they do, adding things and making the board more complex over time.

Usually later version of the board has more columns/sub-columns/lanes/you-name-it than the earlier one. Sticky note bears more information too. Well, if you compare the first version of our Kanban board with the last one you’ll exactly see exactly the pattern.

OK, but where does it bring us?

Considering these two things: we usually don’t really know the process we try to map with the board and the board becomes more complex over time we should avoid over-engineering the board. Start simple and keep it simple. Don’t try to map every possible issue with the initial design of the board.

I would even say that the idea to start with a single “ongoing” column representing the whole process of doing the work is pretty good. You will split it anyway but at least you will know exactly why you’re doing that and which stages you want to make explicitly visible and separated from others.

When crafting your board, if you have doubts whether you should add a column or lane or something or not as a rule of thumb you shouldn’t do that. You’ll do it later… if you really need it.