At Lunar Logic, we have no formal managers, and anyone can make any decision. This introduction is typically enough to pique people’s curiosity (or, rather, trigger their disbelief).

One of the most interesting aspects of such an organizational culture is the salary system.

Since we all can decide about salaries—ours and our colleagues—it naturally follows that we know the whole payroll. Oh my, can that trigger a flame war.

Transparent Salaries

I wrote about our experiments with open salaries at Lunar in the past. At least one of those posts got hot on Hacker News—my “beloved” place for respectful discussions.

As you may guess, not all remarks were supportive.

My favorite, though?

IT WILL FAIL. Salaries are not open for a reason. It is against human nature.

No. Can’t do. Because it is “against human nature.” Sorry, Lunar, I guess. You’re doomed.

On a more serious note, many comments mentioned that transparent salaries may/will piss people off.

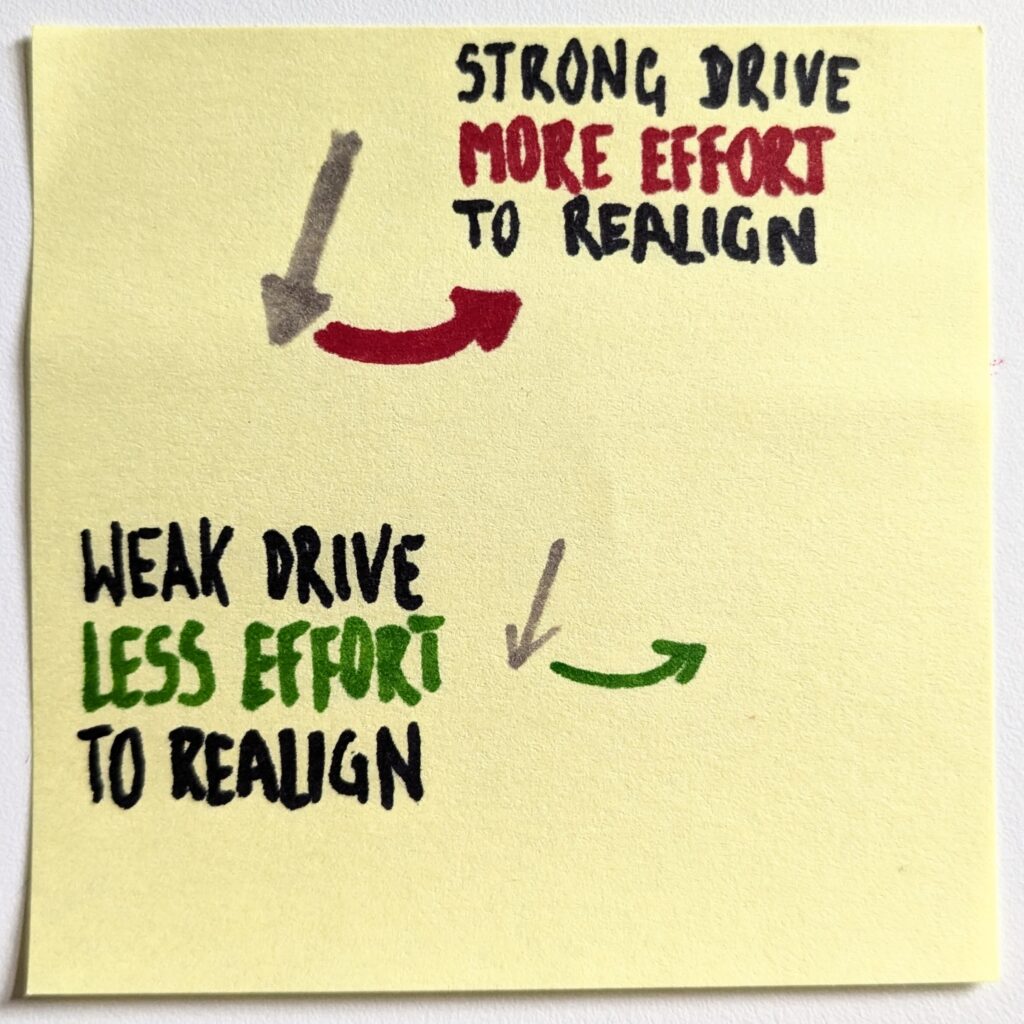

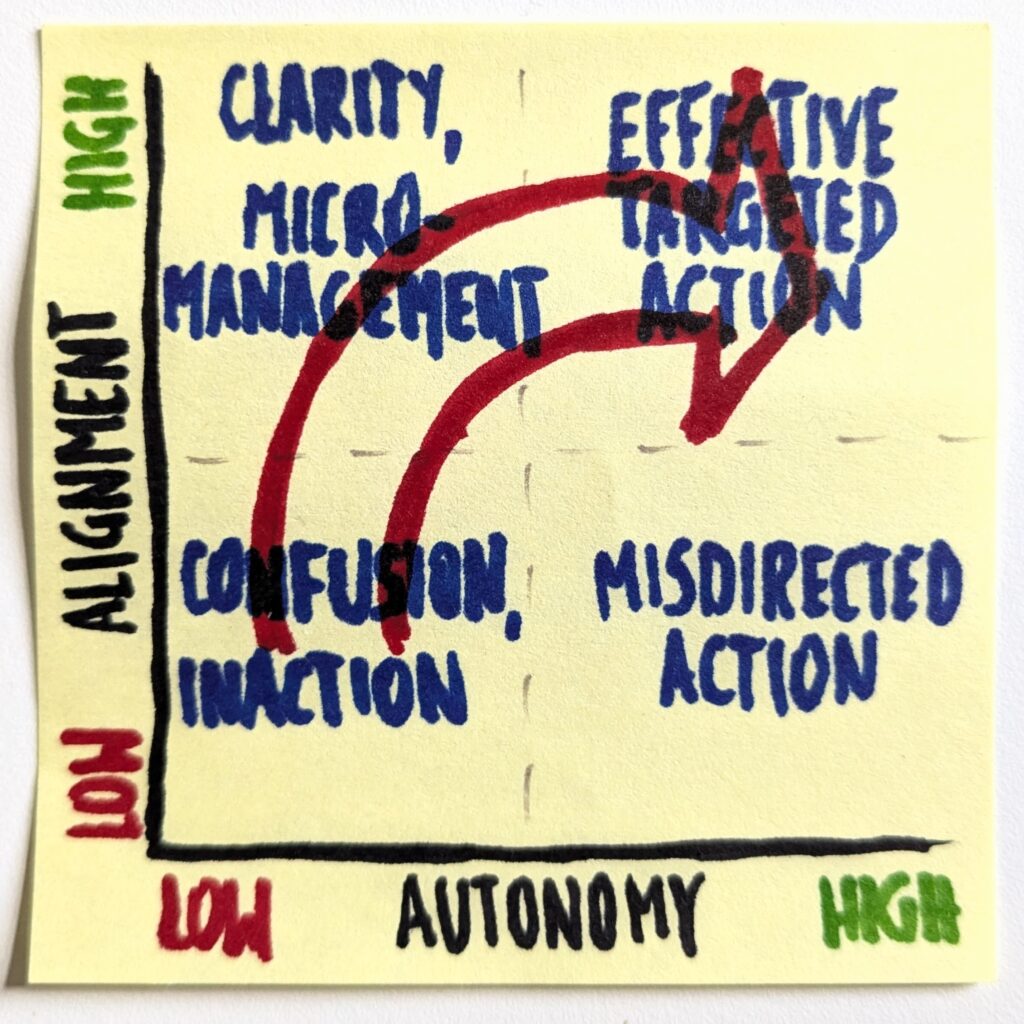

The thing they missed was that transparency and autonomy must always move together. You can’t just pin the payroll to a wall near a water cooler. It will, indeed, trigger only frustration.

By the same token, you can’t let people decide about salaries if they don’t know who earns what. What kind of decisions would you end up with?

So, whatever the system, it has to enable salary transparency and give people influence over who earns what.

Cautionary Tale

Several years back, I had an opportunity to consult for a company that was doing open salaries. Their problem? Selfishness.

In their system, everyone could periodically decide on their raise (within limits). However, each time after the round of raises, the company went into the red. All the profits they were making—and more—went to increased salaries.

The following months were spent recovering from the situation and regaining profitability, only to repeat the cycle again next time.

Their education efforts had only a marginal effect. Some were convinced, but seeing how colleagues aimed for the maximum possible raise, people yielded to the trend.

The cycle has perpetuated.

So what did go wrong? After all, they followed the rulebook. They merged autonomy with transparency. And not only with salaries. The company’s profit and loss statements were transparent, too.

It’s just people didn’t care.

Care

Over the years, when I spoke about distributed autonomy, I struggled to nail down one aspect of it. When we get people involved in decision-making, we want them to feel the responsibility for the outcomes of their decisions.

The problem is that we have a diverse interpretation of the word. I once was on the sidelines of a discussion about responsibility versus accountability. People were arguing about which one was intrinsic and which was extrinsic.

As the only non-native English speaker in the room, I checked the dictionary definitions. Funny thing, both sides were wrong.

Still, I’d rather go with how people understand the term (living language) rather than with dictionary definitions.

So, what I mean when I refer to being responsible for the outcomes of one’s decisions is this intrinsic feeling.

I can’t make someone feel responsible/accountable for the outcomes of their call. At most, I can express my expectations and trigger appropriate consequences.

To dodge the semantic discussion altogether, I picked the word agency instead.

The only problem is that it translates awfully to my native Polish. Frustrated, I started a chat with my friend, and he was like, “Isn’t the thing you describe just care?”

He nailed it.

Care strongly suggests intrinsic motivation, and “caring for decision’s outcomes” is a perfect frame.

How Do You Get People to Care?

The story of the company with self-set salaries—and many comments in the Hacker News thread—shows a lack of care for their organizations.

“As far as I get my fat raise, I don’t care if the company goes under.”

So, how do you change such perspectives?

Care, not unlike trust, is a two-way relationship. If one side doesn’t care for the other, it shouldn’t expect anything else in return. And similarly to trust, one builds care in small steps.

Imagine what would happen if Amazon adopted open salaries for its warehouse workers. Would you expect them to have any restraint? I didn’t think so. But then, all Amazon shows these people is how it doesn’t give a damn about them.

And that can’t be changed in one quick move, with Jeff Bezos giving a pep talk about making Amazon “Earth’s best employer” (yup, he did that).

First, it’s the facts, not words, that count. Second, it would be a hell of a leap for any company, let alone a behemoth employing way more than a million people.

As I’m writing this, I realize that taking care of people’s well-being is a prerequisite for them to care about the company. And that, in turn, is required in order to distribute autonomy.

The Role of Care

The trigger to write this post was a conversation earlier today. We’re organizing a company off-site, and I was asked for my take on paying for something from the company’s pocket.

Unsurprisingly, the frame of the question was, “Can we spend 250 EUR on something?”

Now, a little bit of context may help here. Last year was brutal for us business-wise. Many people make some concessions to keep us afloat. Given all that, my personal take was that if I had 250 EUR to spend, I’d rather spend it differently.

But that wasn’t my answer.

My answer was:

- Everybody knows our P&L

- Everybody knows the invoices we issued last month

- Everybody knows the costs we have to cover this month

- Everybody knows the broader context, including people’s concessions

- We have autonomy

- Go ahead, make your decision

In the end, we’re doing a potluck-style collection.

Sure, it was just a 250 EUR decision. That’s a canonical case of a decision that can not sink a company. But the end of that story is exactly the reason why I’m not worried about putting in the hands of our people decisions that are worth a hundredfold or thousandfold.

We’ve never gone under because we’ve given ourselves too many selfish raises. Even if we could. The answer to why it is so lies in how we deal with those small-scale things.

After all, care is as much a prerequisite for distributed autonomy as alignment is.

This is the third part of a short series of essays on autonomy and alignment. Published so far:

Feel free to subscribe/follow here, on Bluesky, or LinkedIn for updates.

I also run the Pre-Pre-Seed Substack, which is dedicated to discussing early-stage products.