It often comes to me as a surprise that people misunderstand different concepts or definitions that we use in our writings or presentations. Actually, it shouldn’t. I have to remind myself over and over again that I do exactly the same thing – I start playing with different ideas and only eventually learn that I misused or misunderstood some definitions.

Anyway, the context that brought me to these thoughts is slack time. When talking about WIP (Work In Progress) limits we often mention slack time and usually even (vaguely) point what slack time is for. However, basing on different conversations I’m having, people rarely get what slack time is when they first hear about it.

How Slack Time Works

Let’s start with basics. Imagine a very simple development process: we have backlog which we draw features from, then development and testing and after that we are done. For my convenience I split development stage into two sub-columns: ongoing and done, so we know which task is still under development and which can be pulled to testing.

As you might notice we also have WIP limits that will trigger slack time in our process.

In ideal situation a quality engineer would pull tasks from development done sub-column as soon as anything pops there and even if it won’t happen immediately we have a buffer for one feature in development (two developers and WIP limit of 3 in the column). I have a surprise for you: we don’t live in ideal world and ideal situations happen pretty rarely.

There are two scenarios possible here. One is that developers won’t be able to feed quality engineer with features at rate high enough to keep him busy.

In this situation quality engineer is idle. He just face slack time. He can’t pull another task from queue because it is empty so he needs to find a different task. He may try to help developers with their work (if possible) but he may also learn something new using slack time to sharpen his saw. He can also use this time to automate some of his work (and believe me: vast majority apps I saw would benefit heavily from automating some tests) so that the whole process is more effective in future.

Another situation, and the one that is more interesting, would happen when the quality engineer is a bottleneck. It means that he can’t deal with features built by developers at the same rate they are flowing through development.

In this case one of developers who just finished working on a feature has slack time. It is possible that another will soon finish his feature as well and both will be in the same situation. And again, they can use slack time, e.g. to do some refactoring or learn something new or help quality engineer doing his work. However, probably most valuable and at the same moment most desirable thing to do would be finding a way to improve the part of the process that is bottlenecked; here: testing.

The effect might be some kind of automated test suite that reduces effort needed to test any single feature or maybe improvements in code quality policies that result in fewer bugs, thus less rework for each feature.

What Slack Time Is

By this point you should already understand when slack time happens and what it is roughly. Let’s try to pack it into some kind of definition then. Slack time happens when any team member for whatever reasons restrains to do the task they would typically do, e.g. a developer doesn’t develop new features. It is used to do other tasks, that usually result in improvements of all sorts.

That’s a bit simplified definition of course. You may ask what if a developer has a learning task every once in a while put into their queue. Well, I would dare to say that it is just planning for learning and not introducing slack time, but we don’t deal here with strict definitions so I could totally agree if others interpret it differently.

Note: we went through two different root causes for slack time emergence. One is when there aren’t enough tasks to feed one of roles. This is something that happens pretty naturally in many teams. If one of roles further downstream is able to process more tasks than roles upstream (in other words: bottleneck is somewhere upstream) they will naturally have moments of slack time.

Some people may argue that this is not slack time and again I can perfectly accept such point of view. However, for me it suits the definition.

Another root cause is when we intentionally limit throughput upstream to protect bottleneck that is somewhere downstream. This case is way more interesting for a couple of reasons. First, it doesn’t happen naturally so conscious action is required to introduce such slack time. Second, for many people introducing slack time there is counterintuitive, thus they resist to do it.

A result of not limiting throughput before a bottleneck is a huge queue of work waiting for availability of bottleneck role, which makes the whole thing only worse. The team has to juggle more tasks at the same time introducing a lot of context switching and crippling own productivity.

Nature of Slack Time

One of specific properties of slack time is its emergent nature. We don’t carefully plan slack time as we don’t exactly know when exactly it’s going to happen. It appears whenever our flow becomes unbalanced, which sometimes means all the time.

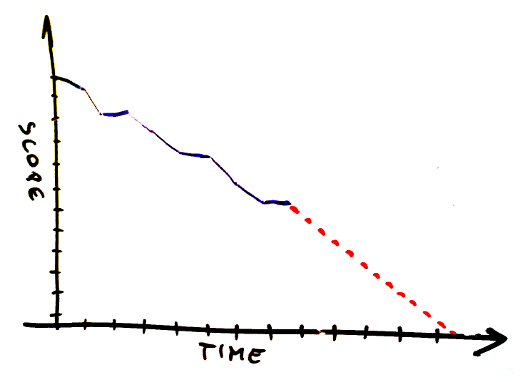

You can say that slack time is some sort of flow self-balancing mechanism. Whenever team members happen to have this time while they don’t do regular work they are encouraged to do something that improves the flow in future, usually balancing it better. At the same time the more unbalanced the team and the flow are the more slack time there will be.

Remember though that in software development business our flow won’t be stable. Even when you reach equilibrium in one moment it will likely be ruined a moment later when you’re dealing with a special case, be it a non-standard feature, a team member taking a few days off or whatever else.

It means that even in environment which is almost perfectly balanced slack time will be happening. Even better, such state means that you don’t have a fixed bottleneck – it will be flowing between two or more roles, meaning that every role in the team would have slack time on occasions.

Another specific of slack time is that usually we aren’t told what exactly we should do in it. It doesn’t have to be that way in each and every case, however since slack time itself isn’t planned we can hardly plan to complete something during slack time in a reasonable manner. On the other hand there may be some guidance which activities are more desirable.

It means that slack time seems to be a tool for teams that trust each other and are trusted by their leaders. It is true as slack time, thanks to its emergent nature, can’t be managed in command and control manner.

However, for those of you who are control freaks, considering you have sensible WIP limits even if your people do nothing during slack time (and I mean virtually nothing) it should still have positive impact on team’s productivity. This is because 100% utilization is a myth. Note that in this case you lose self-balancing property of slack time – you don’t improve your flow. You just keep your efficiency on a bit higher level than you would otherwise.

What Slack Time Is For

I’ve already mentioned a few ideas what to use slack time for. Let’s try to generalize a bit here. Slack time, by definition, isn’t dedicated to do regular stuff, whatever “regular stuff” might mean in your case. If you think about examples I used and try to find a common part these all are important things: learning, improving team’s toolbox, balancing the flow or improving quality.

At the same time none of them seems to be urgent. It is usually more urgent to complete a project on time (or as soon as possible) than to tweak tools team uses or introduce new quality policies.

In short, slack time is for important and not urgent stuff. If something is urgent it likely is in the plan anyway and if something isn’t important what’s the point of doing it.

If you’re interested in more elaborate version of that please read the post: what slack time is for.

Other Flavors of Slack Time

When talking about slack time it is easy to notice that there is some ambiguity around this concept. Why unplanned slack time is OK and planned time slots dedicated to the very same tasks are not?

Personally I’m far from being orthodox over definitions. For me the key is understanding why and how slack time works and why it is valuable, so you can achieve similar effects using adjusted or completely different methods.

Considering that a general goal of slack time is improvement you can introduce dedicated time slots for that or include improvement features in your backlog. The effect might be pretty similar and you may feel that you have more control over a process.

What more, you may want to plan for improvement activities not leaving it to the random nature of slack time. Again, that’s fine for me even though personally I wouldn’t call that slack time.

We may argue over naming, whether something already can be called slack time or not, but I’m not going to die for that really. Especially if we agree on purpose of these activities.

I hope this helps to understand the concept of slack time – what it is, how it works and why it is valuable. Should you have any ideas what is missing or wrong here please leave a comment below. I’ll update the post.