Some time ago, I had a lengthy exchange about how we work at Lunar Logic, which behaviors are OK and which are not. At one point in the discussion, I realized that the source of the different stances in the dispute was a very different perception of what organizational culture is.

Organizational Culture

When I’m referring to organizational culture in my presentations and writing, I typically use quotes from Wikipedia.

“Organizational culture is the behavior of humans within an organization and the meaning that people attach to those behaviors.”

“Culture includes the organization’s vision, values, norms, systems, symbols, language, assumptions, beliefs, and habits.”

Interestingly enough, over the years the exact phrasing of Wikipedia article on organizational culture has evolved so you won’t find identical words there anymore. Either way, the original quotes stand the test of the time.

If you need a more concise definition, I could propose something like “a sum of behaviors of everyone in an organization, or a part of it, and the reasons behind these behaviors.”

Even shorter: “how everyone in a group behaves and why.”

Building Blocks

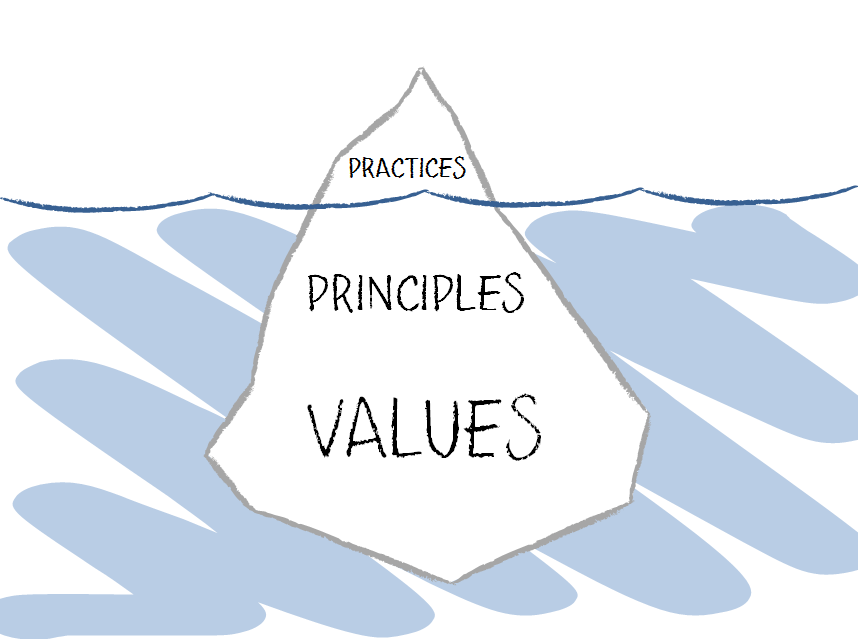

From the perspective of a person who wants to learn an organization or to influence the culture shift, not all the building blocks are equal. It is near impossible to change people’s fundamental beliefs or core values. It is neither easy nor fast to alter subconsciousness. Habits, assumptions, and perceived systems often reside in the subconscious part of our thoughts.

What’s more, all of the above, except for some habits, aren’t easy to spot. Ultimately no one has their core values tattoed on their forehead, and very rarely we are aware of these inner drivers of others’ behaviors. It’s no wonder. No one teaches us to pay attention to that.

The most visible aspects of culture, and thus, the easiest to work with, are rules and norms, respectively. Rules, by definition, should be written down, so they are accessible to anyone interested. Norms are a bit trickier since they’re defined by what people believe is, or is not, appropriate. Either way, if one pays attention, it is not hard to derive organizational norms by merely observing what people do and what they do not.

The Role of Observation

Let’s assume that you’ve just joined a new company. You enter our office cantina and see me having a beer with my lunch. You realize that there was nothing about that in the rule book you read during the onboarding. However, a societal norm is that we don’t drink alcohol during work hours. How do you react? Most likely, you look at other people to probe their reactions. If they ignore my behavior altogether, it appears that it is OK for me to have a beer during lunch.

Note: it’s too little to tell what the norm is yet. It’s a decent first step, though. You may still want to watch whether other people do the same thing or instead I am a special case, and I can do things others can’t. Oh, and it may be relevant whether a beer was a regular or non-alcoholic one.

Either way, eventually, you have a good sense of whether you (or anyone else) can safely have a beer for lunch. You will derive that knowledge by merely observing and absorbing the environment around you.

Observation is indispensable too in the context of rules. Something can be written down as a rule and still get ignored. We could tweak the story above so that there is a rule, e.g., in the employment contract, that explicitly states that drinking alcohol at work is forbidden. This way we’d have a situation when a norm (having a beer with lunch is fine) contradicts a rule (it is prohibited).

The outcome would be the same altogether. The norms trump the rules. Without observation, it is neither possible to figure out the norms nor to learn which rules are there in the name only and which are the law.

Figuring Out Organizational Culture

If one aims to understand the organizational culture of a company they just joined, there is no real shortcut that would be an equivalent of prolonged observation. Some tricks may hasten the process, of course. Not too much, however. You can’t learn the organizational culture in several weeks. At best you can familiarize some parts, but it would be far from a complete picture.

Again, let’s imagine that you’ve just got hired. You joined a team of five, which is a part of a division of 40-something, and the whole company is around 200 people. Figuring out how to safely operate and behave in the closest neighborhood — your atomic team — should be a straightforward process. You’ll get plenty of opportunities to observe, and feedback loops will be short. You’ll have validation paths readily available through the means of chatting with your team lead and your peers.

This way, you would explore, however, only one small area on a big map of organizational culture. Yes, it is by far the most important for your everyday work, but hardly enough for a complete understanding of how to act in all situations, including some that may get you fired.

There are interactions within your division, both cross-team and division-wide. There are all sorts of rules and norms that apply to a company as a whole, or specific ranks, or even particular people. Discovering all these uncharted areas takes time.

The Tricks

There are a few tricks that can speed the exploration a bit. By no means, they are a substitute for awareness and observation, but they help.

The higher up in the hierarchy someone is, the bigger their influence over the culture. To get a roughly accurate, even if a vastly incomplete and imprecise, image of the organizational culture, you could shadow the company’s CEO for some time. Since the behaviors of higher ranks often get copied at lower levels, a sneak peek at the very top of the hierarchy gives you a potentially most statistically significant representation of the culture.

Ignore officially expressed company values, its vision, or a mission statement. It is such a rare case that a company indeed follows an aspiration expressed in either of them that they most usually are a source of noise, not signal. Look at the actual behaviors, not aspirational statements.

Seek conflicts and watch how they get resolved. Controversial situations require parties to take a stand, and thus, they trigger action. On such occasions, it is easy to see who calls the shots and whose opinions count. The friction that is an integral part of any conflict is a natural fuel for shaping and reshaping norms, challenging rules, and expressing less visible drivers of the culture: values, beliefs, and assumptions.

Ultimately, though, there’s no better trick than patience and perceptiveness.

Crucial Role of Understanding Culture

OK, but why is understanding the organizational culture so important? Unless we have a good grasp of it, we are bound to either traveling only through well-beaten paths or risking frustration.

Well-beaten paths are safe. It’s easy to follow what everyone else is doing. It means, however, that our influence on the organization would be limited to the face value of our everyday contributions. We wouldn’t be challenging or changing our team and our company. Typically, that’s perfectly fine, even expected, during an initial period at any organization. Later on, not necessarily so. At least not in a firm that hopes to use the potential of its people.

The other scenario is quickly jumping to the acting mode, challenging rules, status quo, opinions, behaviors; it’s a departure from a beaten path. The problem is when such a departure happens in uncharted territory. There are things which are appropriate and those that are not. There are norms, beliefs, assumptions, and values. Blindly flailing around means that we would inevitably violate these informal constraints.

This way we will, of course, uncover the part of the uncharted territory, but the price is high. One part of it is frustration: “Oh, we don’t do such things here; I wasn’t aware.” The other part is reputation. Opposing or challenging things with little effort to understand them first doesn’t score much respect. There is a world of difference between being a contrarian who understands the culture and one who doesn’t.

If we aspire to influence organizational culture eventually, learning it first is a crucial and obligatory prerequisite.