We can consider so many things both in our professional and personal lives as value exchange. The most obvious case: I exchange 40 hours of my time each week for a set amount of money that lands in my bank account each month.

As a business, we do the same thing. We commit our engineers to spend their time on whatever our clients need them for, and in exchange, we receive an agreed-upon rate for each hour of that effort.

In fact, I often use that frame when describing how we perceive our contributions. We aspire our clients to be happy with the value we deliver for the price they pay for the whole team.

What Is Value?

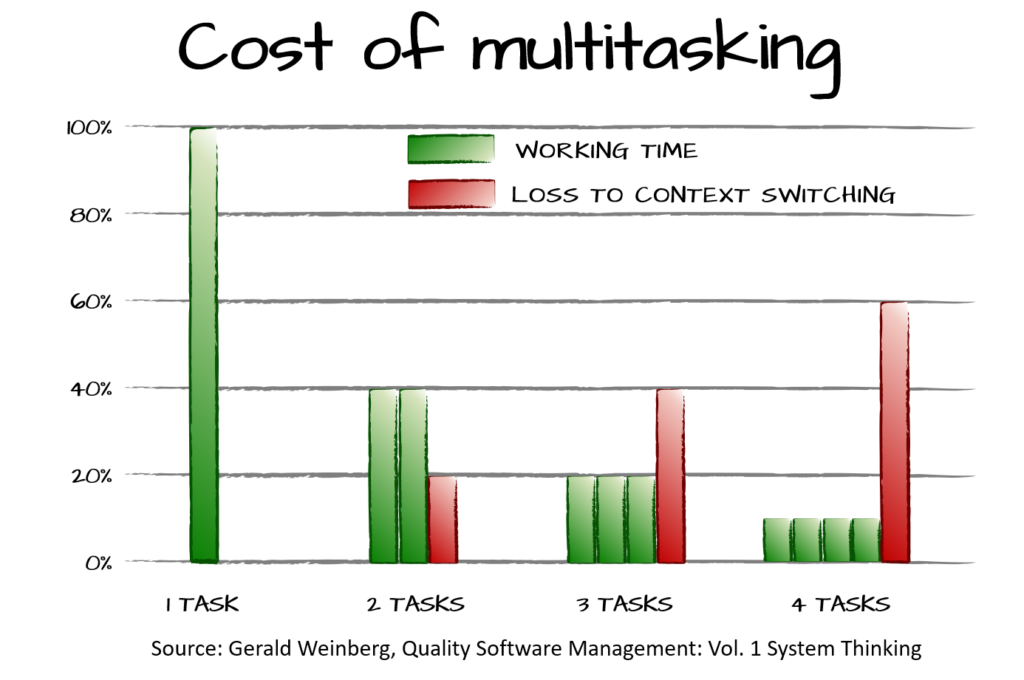

Now, the tricky part in these examples is value. While we can easily assess how many hours anyone spends on a task, the time doesn’t automatically translate to value. What’s more, it’s not even purely a matter of how one will spend that hour.

I can work on an activity that has only certain odds of success. If the outcome ultimately emerges as a failure, no value will have been delivered. The reasons for that may be entirely outside my sphere of control.

As an example, think of all the effort I invest into helping a potential client improve how they will approach building their new product just to see them choose a different partner. In this case, my work has not yielded any value for Lunar.

However, even if I work on something that we assume to have intrinsic value, it’s still tricky. Let’s look at adding a feature to a product. (And yes, I know that not every feature is value-adding. In fact, there are some whose net value would be negative.)

Assuming the feature I’m building will have a positive effect, the big question is how big of an impact and how much our client values it. That question is almost universally highly challenging.

Most of the time, we can’t know the answer upfront. We need to build the thing to be able to validate the outcome. Most of the time, however, we don’t try to check that anyway. Even if we did, most of the time, the early validation will now give the complete picture.

Think of The Shawshank Redemption. Its theatrical release was largely a flop. And yet, over the years, it gathered a strong fanbase, still keeps the #1 position as the best movie ever at IMDB, and eventually, it at least paid off production costs. Not a bad outcome for a flop, eh?

While there obviously is a correlation between the opening weekend box office and the eventual financial success of a movie, we can’t precisely know the financial success/failure just after the first few days.

The same goes for value assessment in most of the knowledge work. You could just as easily consider whether paying an employee any specific salary yields a valuable (enough) outcome. And the smaller chunk of work you look at, the more the mileage will vary.

Making Value Exchange Work

We use two basic coping mechanisms to work around uncertainty about value.

The first one is ignoring the actual value altogether and sticking with our early assumptions of what we expected it to be. It’s like deciding to build that feature because “it will bring us so many new subscribers” and never looking back. Sure, before committing to the development, we might have asked for an estimate. If it was acceptable enough (and the work didn’t take much longer), it was the last time we did any assessment of the work.

We thought it would bring us a ton of subscribers, and it was a sound decision to pay $10k for that. Oh, and since we already paid for that work, who cares whether it actually brought a single new soul to our solution?

Well, I’d say this means giving up on a ton of learning here, and that’s of huge value by itself, but I clearly must be wrong, as very few product organizations do any post-release validation.

The second way to dodge the uncertainty of value is by looking at a bigger whole. I don’t try to assess whether an engineer has been productive during every single hour or day. Heck, I’d be perfectly fine with a slower week, too. However, I want to know whether their long-term performance justifies their salary.

By the same token, I want the whole team working for a client to deliver good value for money in the long run. So, if we look at the weeks or months of work of the whole group, we are happy with the value of everything they deliver (of course, in the context of what that effort costs, again, in total).

In extreme cases, you could look at movie studios or VCs investing in startups. They are happy to weather plenty of bad investments as long as that one movie or that one startup yields a 100x or more return.

Lateral Skillsets

We all make one subconscious assumption here. That is, even though we exchange different things, they are of similar value for both parties. If we ask for $90 an hour for our developers, that hour would be priced roughly a similar way, whether by Lunar’s client or me. Or rather, we would price the skills our client rents for that hour similarly.

This assumption, though, often doesn’t hold true.

To stick with the engineering/software development context. When our potential clients want to assess our team’s skill set, it will almost always be heavily skewed toward technical skills. After all, when you hire developers, they will do development, right?

But let me redefine the situation here. Imagine you seek someone to turn your idea into an MVP. You have two candidates with very similar technical skills. However, one builds their experience by working on many different small engagements, including several very early-stage products. The other spent big chunks of their time working on very few large and complex solutions.

Which one would you choose?

I bet most of us would go with the former over the latter, as we’d deem their experience more relevant. This relevancy, however, stems from a lateral skillset. It’s not an ultimate value. It’s value in the context.

Product management skills may actually emerge as the most crucial for that role, even if we don’t consider it so upfront. At the early stage of product development, building the wrong thing is rarely salvageable. Building the thing wrongly, on the other hand, can typically be saved.

If we had considered a different gig, we might have chosen differently.

This is but one example of lateral skills that may make or break any endeavor. A broad range of people skills, project management savvy, business context understanding, and more may be similar game-changers here.

And yet, without the specific context, the broad market would largely ignore those traits. Even within the context, they are most often omitted.

Asymmetric Value Exchange

The lateral skills are what change the economy of the whole value exchange. The job market would value two similarly technically skilled developers, well, similarly. After all, across a wide variety of challenges, they will provide comparable value.

However, within the early stage product development context, the first one will deliver something extra. They wouldn’t be working extra hours, their code wouldn’t objectively be better quality, they wouldn’t be faster.

Yet something that costs nothing extra to that developer–their lateral early product management skills–would be highly beneficial for the product company.

That’s what breaks the simple economy of value exchange. I add to the mix something that’s of little to no cost for me but gives the other party a big upside.

In other words, I give up nothing while they gain a lot.

Suddenly, the whole deal has so much more wiggle room, which can be used to make it more attractive for both parties.

Not only that, though. It also generates additional options for value delivery. Our developer may use their time building a feature that ultimately will not help. However, thanks to their experience, they can also suggest (in)validating the whole part of an app prior to committing to development. That, in turn, may lead to much more significant savings.

In this case, exploiting lateral skills makes the value exchange asymmetric. Why is it important? It’s because whenever you can find a partnership with an asymmetric value exchange, it’s a plain win-win scenario for both parties.

Since lateral skills typically create these scenarios, we should pay much attention to them.

Side Skills Are Core Skills

If I looked for a technical partner to help me with an early-stage product, I would primarily be looking for stories about discovery work, building MVPs, validation, etc.

As a matter of fact, I’d be explicitly asking for failure stories. I mean, we know the data. New products do fail. So, if the only thing someone has to show is a neat streak of successes, you can be sure they’re in a fantastic realm.

One of my mantras is, “Many of our past clients paid us to fail, so you don’t have to. You get all the experience we got from that as a part of the package.”

These lessons do not fall into what’s commonly perceived as “core skills” for software development teams. And yet, we do consider them core. We shine most when we’re able to utilize those side skills.

So, go figure out what constitutes those lateral skillsets in your context. These are the core traits you should be looking for, whether hiring or choosing a partner in your endeavors.