It seems my Milk Kanban article has made a stir. I kinda expected some backlash along the “it’s not really Kanban” lines. However, when the post hit Hacker News, I got a swath of remarks attacking it from a different angle.

The problem is, as the comments go, that someone’s job is outsourced to random colleagues. In this case, it would be Kasia (our office manager) outsourcing her job (ensuring that the office is supplied with milk) to macchiato drinkers who can’t be bothered because they have more important stuff to do.

Oh boy, where do I start?

Get Out of Your Cave

It took me quite a while to grasp that some commenters perceived managing the milk supply as a priority job for an office manager.

Yes, I know our context so much better; we’re a small company, and everyone wears multiple hats. But even in big organizations, I’d be shocked if such a matter was anyone’s top priority.

For Kasia, it’s like the 100th thing on the list of stuff she takes care of.

But again, even if we consider a generic example, it would be so easy to figure out how many things, big and small, an office manager takes care of. Then, there’s probably twice as much of stuff that’s not visible on the surface.

I mean, any developer, whose primary task is working with code that’s inherently invisible, should grok that concept.

Effectiveness versus Efficiency

However, then things only get more interesting. Even when people considered doing something to help, they’d instantly play the efficiency card.

“I can’t be bothered to let someone know that we’re running out of milk because I’m doing this important work, and me being a 10x developer requires absolute focus.”

Weird that they have time for a coffee break then, but what would I know?

But yes, having someone do 30 seconds of work, which may save someone else 10 minutes, is a sensible tradeoff. Even if the latter is paid less. Even if that half a minute wouldn’t be efficient.

That’s the most basic effectiveness versus efficiency consideration. I can be efficient as hell, but unless we, as the whole team, can reliably deliver value, it doesn’t matter.

It’s the equivalent of a developer whose coding pace would be fabulous, except there would be no one to code review or test their features. They may feel like they were being productive. The team, however, would be so.

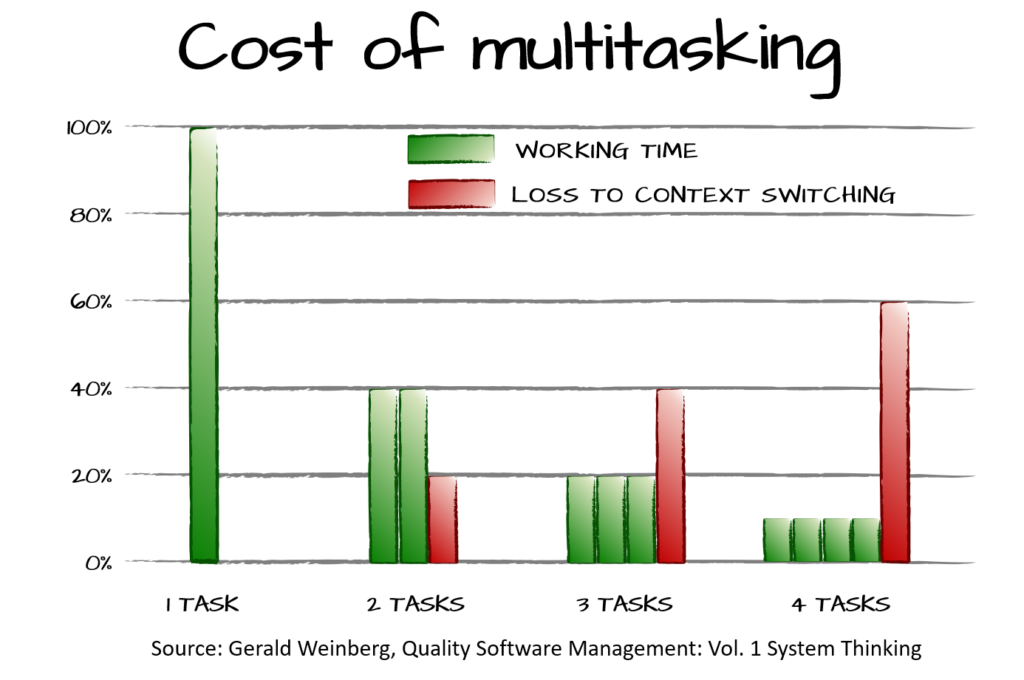

In fact, the amount of work in progress they’d introduce would make the team less efficient. It would introduce more multitasking, more rework, and more context loss.

One has to wonder whether people showing such a lack of understanding of how the whole organization delivers value should really be valued as highly.

A narrow focus on efficiency, especially in an isolated context, is typically detrimental to the effectiveness of the whole process.

Respect

However, if anything in that discussion makes me sad, it’s the lack of respect.

“If checking the milk reserves once a day is too much of a pain for a person hired as an office manager, the person should self-reflect on his/her choice to take the job.”

And that comes from developers, a group that is notoriously crappy at filling time tracking data, even when companies rely on that data to bill clients.

However, my beef here is with a lack of respect for another job. Yes, this job is not paid as well. But I’m sure as hell that as much as an average office manager would fail miserably if they were to do software engineering, an average developer wouldn’t fare better in an office manager’s shoes.

In our case, just as an example, we’re yet to have a single foreigner who wouldn’t be deeply grateful to Kasia for help with all the formal stuff related to employment papers, work permits, etc.

In fact, it would be easier for us to lose a couple of our best engineers than to lose Kasia.

The point is, though, that it doesn’t even matter whether we really understand someone else’s job. It matters whether we respect it as a part of the bigger whole.

If not, it’s easy to boil it down to “I want my goddamn coffee to have milk, and someone better make sure I have it.” It’s easy to subordinate everyone else’s work only to whatever I might need of them. Then, of course, people won’t be willing to spend half a minute helping anyone with anything. Even if that someone makes sure that the milk is in the cupboard.

I understand that in many companies, this is the norm. People are not respected, and, in turn, they don’t respect others. They won’t be willing to help with anything that’s not explicitly their assignment.

It’s not a Milk Kanban problem. It’s a (lack of) respect problem.

Now, establishing respect as a part of organizational culture is so much harder than making the milk supply work effectively.

Wrap Up

I understand the specific context of these comments. The software industry made us, in a significant part, spoiled kids. It’s still easy to sustain a lucrative career by focusing only on one’s technical skills, individual tasks, and not much more.

I’m not necessarily surprised by how the comments disregarded the work of others, the broader context, and common goals. The sentiments, though, are not unique to software developers. I see a lot of similar attitudes in management.

And the ways of dealing with the issue will be similar. Understand others’ roles and jobs. Understand the difference between group effectiveness and individual efficiency. Most importantly, respect others and their contributions.

Milk Kanban or not, it’s easy to get enough milk in a cupboard. Building a culture of respect, on the other hand, is damn hard.

And it starts with the very people who have disproportional leverage on the organization. Yes, the same folks who tend to earn more and fill the most prestigious roles.