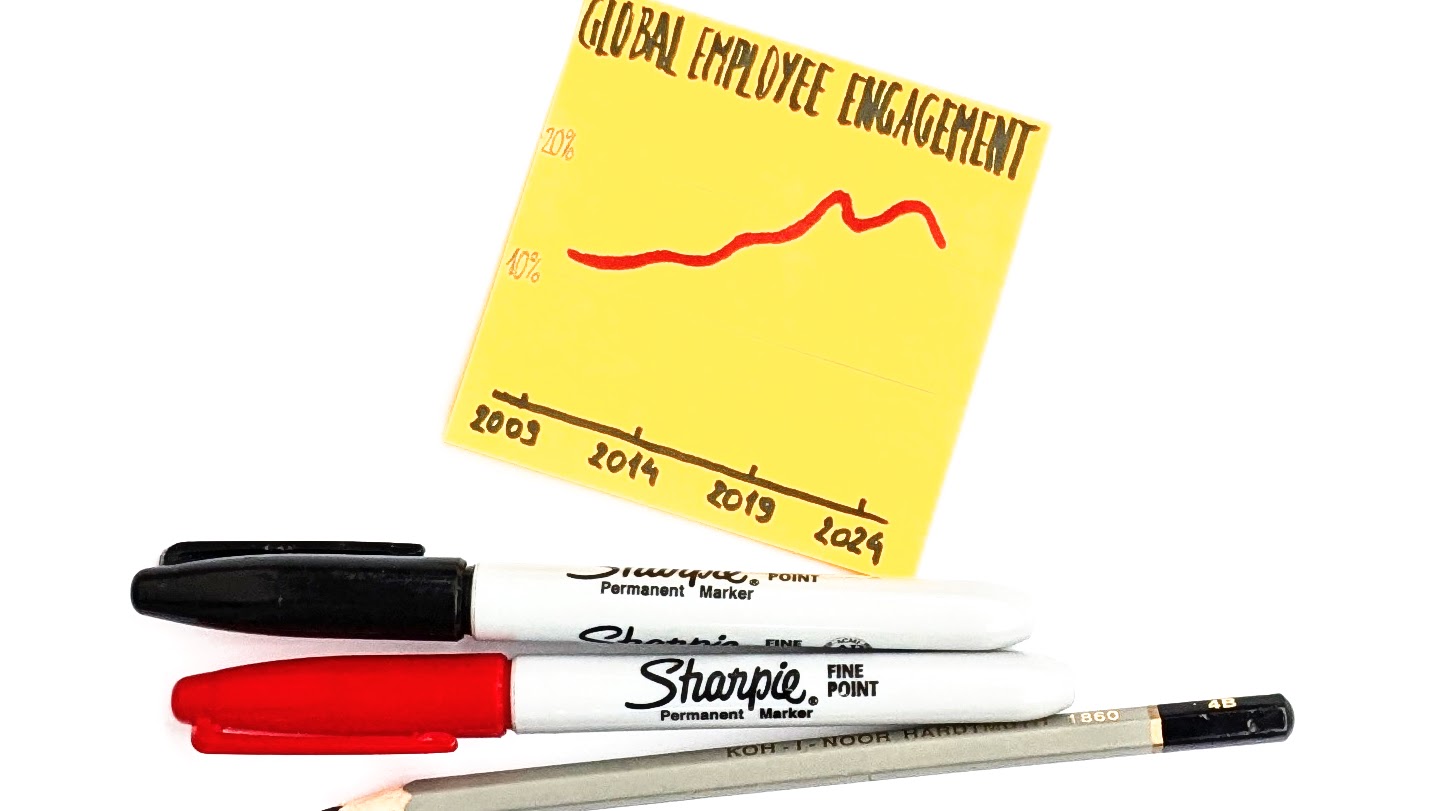

Last time, I built the connection between distributed autonomy (or lack thereof) and engagement (or lack thereof). Admittedly, I drew from different sources, and one could question some claims or connections I made.

- I mix engagement and motivation, and they are not simple substitutes for one another.

- Gallup’s State of the Global Workplace has faced some criticism for not actually asking about engagement, but instead inferring it (by the way, this book explains the methodology behind the research).

- We all have anecdotal stories about limited-autonomy environments where engagement doesn’t seem to be a problem.

So how is it, really? Do we really feel more engaged when we have more control over the work we do?

I have the privilege of running the course on progressive organizations in all sorts of settings, from MBA programs, through postgraduate studies, to professional training. As a part of the course, I designed a little experiment to run with all those different crowds. Over the years and across contexts, it keeps telling the same story.

What Can LEGO Teach Us About Autonomy?

The experiment is fairly simple. I get a group of people to build a relatively simple LEGO set. Twice.

The Managed Build

The first run is well-organized. We pick one team member as a manager, who starts by assigning tasks to the rest of the team. A typical team member’s job would be to:

- Be responsible for a specific type or color of pieces.

- Build a particular part of the model.

- Etc.

Over the years, I experimented with how much freedom a group’s manager has in organizing work. It doesn’t seem to matter. What’s important here is that the whole work organization is designed by—and, to a degree, enforced by—a single person.

Then they get to build a catamaran. With instructions. Displayed on a screen. With me controlling the pace. Actually, it’s they who control the pace. I “flip” the page once the last team is ready.

Eventually, all the teams build perfect catamarans. Up to specs. There are some subtle challenges in the process, but that goes beyond the context of autonomy versus engagement.

The Self-Organized Build

The second run is different. There aren’t managers anymore. There is no task assignment pre-building. The whole instruction is: “Self-organize.”

There is no instruction either. The only thing a group gets is the picture of a hydroplane they’re building.

People have all the freedom to organize their work. Sometimes they do plan. Much more often, they don’t. A creative and messy process commences. Inevitably, it’s all louder and more chaotic than the first run. On average, it’s a bit longer, too.

Eventually, I get my hydroplanes. Some of them perfect. Others not so. However, I’m yet to receive one that differs from the picture in anything other than minor details.

The Lesson

While there are many facets to this experiment, the big lesson is about engagement. After each run, I ask everyone individually to assess their engagement during the task on a scale from 1 to 5:

- Very low

- Rather low

- Neither low nor high

- Rather high

- Very high

The underlying hypothesis is, of course, that the second run, the one where people have more autonomy, yields better engagement.

Across all the teams that have ever participated in the exercise, the current running averages are:

- 3.24 for the managed build

- 3.94 for the self-organized build

There wasn’t a single experiment in which teams were less engaged in the second run (though in one case the results were close—0.14 difference).

In other words, I’m yet to see a group of people who would be less engaged in a creative LEGO build when they were given more autonomy.

Some Experiment Caveats

One important aspect of the experiment design is that the models are relatively simple, while I organize people in groups of 4 or 5. As a result, there are too many hands for the task. It is so by design. It’s an environment where it’s relatively easy for people to disconnect, should they choose to.

Also, it’s LEGO. For some people, it will be inherently engaging no matter what. They tend to take an active part in the first run, disregarding their assigned role.

Those two aspects of the game create an environment in which people use the full scale when assessing their engagement. I’ve only had one group that hasn’t used 1s at all. Possibly too many AFOLs in the room.

The pace of flipping the instruction pages in the managed build tends to be a minor source of frustration for faster teams. Again, that’s by design. It’s just another dimension of limited autonomy. After all, with real work, we have all sorts of interdependencies.

A side note: Interestingly, it’s not always the same team that is the slowest throughout the whole run. It’s a classic case of a shifting bottleneck.

Distributed Autonomy Is a Crucial Prerequisite for Engagement

My working hypothesis is that the main reason behind appalling engagement levels is limited autonomy. The theory suggests as much.

The LEGO experiment is a neat way to confirm that in practice. With a simple change of giving people more autonomy, the declared engagement goes up by more than 20%.

The observable behaviors are different, too. The managed build generates way less energy, fewer discussions in teams, less movement across the room. If you saw randomized silent movies (no audio) from the respective experiment runs, it would be obvious which is which.

Distributed autonomy—being able to decide how we work—is an absolutely crucial aspect of our workplaces. And a prerequisite for high motivation and engagement.

This is part of a short series of essays on autonomy and how it relates to other aspects of the modern workplace. Published so far:

- Pivotal Role of Distributed Autonomy

- Role of Alignment

- Care Matters, or How To Distribute Autonomy and Not Break Things in the Process

- Limited Autonomy Is the Main Reason for Low Engagement Levels

I’m writing these posts by hand. Like an animal.

웃https://okhuman.com/NbZHoQ